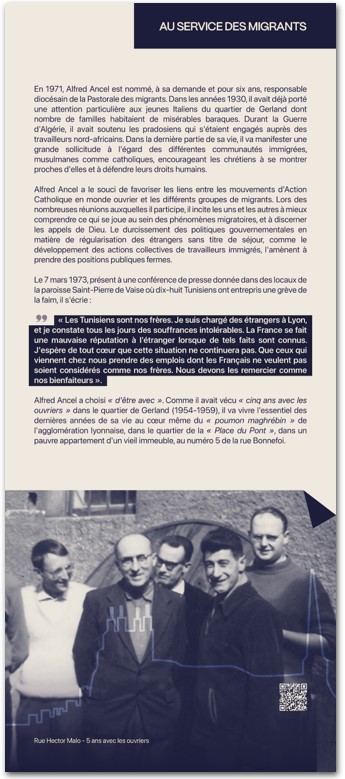

In this text, you will find some details about the work experience of Bishop Ancel as employed by Établissements T. David in Gerland from 1954 to 1959.

The following information was gathered by Pierre David in 1984, on the death of Mgr Ancel, to his father, François Davidwho was the manager of the company that hired him at the end of 1954.

When we visited him at the Ehpad in Mâcon, Pierre gave us a copy of the manuscript he had written at the time, which was kept in his archives. We added a few historical and technical contextualising elements to it, which he had described in a second memoir devoted to the other textile recovery and polishing disc workshop, Madame Chapolard's in Saint-Fons.

Direct testimonies, following the perception and memory of the entrepreneur, three decades later, transcribed and formatted by Pierre. New material that will be of interest to readers.

"It was at the end of 1954 that Monsignor ANCEL came to look for work in the factory that I ran with my brother Jean DAVID. He had obtained authorisation from Rome, within the Prado community, to try a new pastoral experience in the working world through sharing the working conditions. However, Rome imposed one restriction: the work had to be done at home, not in a workshop or factory.

Monsignor ANCEL came to Gerland, where our factory was located, on the recommendation of Father CAPTIER, a pradosian priest, who was responsible for the Saint-Léonard house in the commune of ALBIGNY-sur-SAONE (69).

We had already had links with the PRADO for a long time. The DAVID family, who lived at 9 place Raspail in Lyon, had a good relationship with the Prado priests in charge of the family parish: Saint-André. What's more, before moving to Gerland shortly before the war, the craft workshop was located on rue Montesquieu, and it was not unusual for it to take in "protégés" of Sister Anna, whose mission was to help prostitutes who wanted to "quit hooking".

In addition, during the Occupation, the company benefited from the support of Prado: to prevent our stock of fabric from being requisitioned by the Germans, we hid some of it in our premises in the rue du Père Chevrier; above all, as part of another metal refining activity, before the war the company had acquired a large quantity of used nickel anodes, in the form of crushed scrap metal contained in heavy iron drums; An order issued by the Vichy regime obliged all companies to declare their stocks of non-ferrous metals, which my brother and I had refused to do; but then another order was issued by the Kommandantur on 1 January 1949.er The aim was to requisition stocks of non-ferrous metals in the first quarter of 1943, and to search companies likely to be in possession of them... Once again, some of the barrels made their way to the Prado house.

With the Liberation and the end of the war, the company was able to resume its activities, particularly those of our products that used recycled fabric: rags, old clothes and sheets, military blankets, etc. These fabrics of all kinds were delivered in bales of heavy, coarse jute cloth, which had to be torn open before being sorted: on the one hand, the "noble" pieces, the largest ones, from which it was possible to cut out flat areas and squares of fabric that would become polishing discs; on the other hand, those that became "wipings" resold to garages, printers, etc., all people who were constantly working with a rag in their hand; Finally, there was the pile of "frayed" fabrics, which could be carded with metal brushes and unravelled to produce a mat of intertwined fibres held together by simple parallel overlays.

This is where Father Captier and his Maison de Saint-Léonard come in. In fact, we provided this type of work, including the transformation of the "noble" part into polishing discs, to the workshop run by Father CAPTIER for former common law prisoners or political prisoners (collaboration), beneficiaries of remissions of sentence, under house arrest or subject to a ban on residence, who found refuge at Saint-Léonard.

Sorted and then cut into squares, the panels of fabric were mounted by successive bias cuts on a crown of pins, to form a mattress that a snail stitch held together, ready to become wheels of different thicknesses but perfectly circular after die-cutting.

Visiting this workshop, Monsignor ANCEL, Auxiliary Bishop of Lyon and Superior General of Prado, had the idea that the work carried out here might be suitable for what he was authorised to do: it could be done at home; it could be paid by the piece; the head of the company and Prado had known each other for a long time; the company was located in Gerland, close to the place where the small working community he was leading had been established to live this experience (two brothers working full time in a factory and two priests working three hours a day in small companies).

That's how Monsignor ANCEL came to ask me to take him on as a home worker. I agreed, but told him straight away:

I will quickly note that, for these various reasons, Alfred ANCEL achieved an output of 1, whereas a slightly experienced worker in Madame Chapolard's workshop in Saint-Fons (another workshop I supplied) achieved 2.2 or more.

After I agreed to take him on, Monsignor ANCEL asked me where he could "learn the trade". I suggested he could do it at the Gerland factory, or with the women in the Saint-Fons workshop, or if he preferred, at Saint-Léonard with the "prison leavers".

This was the solution he adopted.

His apprenticeship, moreover, gave rise to an anecdote which Father CAPTIER later told me, when I asked him how his "boss's" training had gone:

A crude assessment, no doubt, of the mediocre skill and low output obtained by Monsignor ANCEL in the exercise of manual labour.

After this "training", every fortnight or so, the factory driver would go to Monsignor ANCEL's house in the Gerland community to collect the finished work and bring him the bales of rags that made up the raw material. This shuttle service lasted for almost 5 years.

On the other hand, he would come to the factory himself to get paid. There, everyone knew who he was, the auxiliary bishop of Lyon, and everyone called him Monsignor. It was Fellah, a North African who had worked at the plant for a very long time, who weighed his work, and the secretaries drew up his payslip. His status was that of a home-worker, paid on a piece-rate basis; he paid social security contributions like any other employee.

Usually wearing a black jacket, dark trousers and a black beret, he would come to collect his wages, either on foot or by bicycle. This was often an opportunity for him to talk to people. These contacts, although episodic, certainly forged quite deep bonds. For example, when one of the two secretaries had to be hospitalised, he went to see her in hospital, and she was very touched.

Was he able to discuss religious matters or the role of the Church with the factory workers?

What is certain, however, is the genuine sympathy he aroused, including among members of staff who were totally alienated from Catholicism.

With me, or with my brother, Monsignor ANCEL had the opportunity to raise the question of his involvement. Personally, I was opposed to this type of presence. I felt that a bishop's place was not there, and I told him so. For him, it was the only way to really get in touch with people in the working world. But most of the time, we talked about economic problems, about what he was also discovering during some of the trips he had to make.

One point we have often discussed is the responsibilities of employers. I was very keen that Monsignor ANCEL should discover the image of an employer whose sole concern is not personal enrichment and the exploitation of workers. In fact, I had reacted on this subject to what I thought was a very simplistic statement by Cardinal Gerlier, by writing him a letter which never received a reply... I took the liberty of saying to Monsignor ANCEL on one occasion: "Monsignor, when you've finished your experience as a bishop-worker, I'd like you to experience what it's like to be a bishop-manager, so that you can judge!

In fact, I felt that some of the Church's positions, systematically favourable to the workers' movements, were unfairly biased in relation to what I was experiencing or trying to achieve on a daily basis.

The time when Monsignor ANCEL worked with us was also the time when the Algerian war began. In all that time, I never had the opportunity to speak with him about this issue and the political choices it gave rise to.

I am also unaware of any links the Gerland community may have had with certain members or supporters of Algerian political networks. The only discussion I can remember about Algeria concerned a convergence of views on solutions combining crafts and farming in Kabylia. We got to that point from a discussion about peasant workers in the Ardèche. It seemed to me to be a fundamental debate for the modernisation of Algeria. The option, totally opposed to this perspective, of large industrial complexes, was taken...

I went several times to the Gerland Community, to deliver the bales and load the work carried out. I sometimes arrived at mealtimes, and was invited to share them. It was fine, and always accompanied by a huge salad. The workshop was on the ground floor, next to the kitchen where meals were taken. When Monsignor ANCEL worked in this workshop, he would pull his beret down over his one-eyed eyelid: he had removed his glass eye, because the dust caused by handling the rags could irritate his eye socket.

I had the opportunity to see him on other occasions, including the confirmation of one of my daughters at the Sainte-Croix parish. He officiated with Monsignor Bornet. At the end of the ceremony, I went to greet him in the sacristy. He was very cordial and said to me: "Well, Mr David, what are you doing here? And introduced me to all those present as his "boss"!

A response typical of his simplicity.

Our last meeting was in Gerland, when he came to tell me about Rome's decision to prohibit the continuation of the priest-worker experiment. He had come to the factory to sort out his social security papers and clear up his file.

After that, I think he travelled a lot to various countries, including Japan, and we never saw each other again, except during a trip I made to Toulouse when he was on his way to Lourdes.

Interview by Pierre DAVID with François DAVID, company director, Toussieu, November 1984.