Alfred Ancel (1898-1984), priest of the diocese of Lyon (in 1923), general manager of the Association des Prêtres du Prado (1942-1971), auxiliary bishop of Lyon (1947-1973).

He has been a member of the French Episcopal Commission for the Workers' World since it was founded in 1950, and chaired the commission in 1964 and again in 1967. In other words, Alfred Ancel's career covers a large part of the history of priests-workers, and here is a brief overview, from 1944 to 1974, in four periods: 1944-1947; 1947-1954; 1954-1965; 1965-1974.

For each of these periods, the contexts are not specified so as not to make this article too long (economic, political, social, cultural, religious, ecclesiastical context), but they are part of this history and would help to understand it. What's more, this overview is only part of the real story. To talk about the history of the P.O. would be to talk about their ordinary lives among the people, in the working class, in working-class environments, in local Churches, to talk about what they lived, did and thought, to talk about their daily lives, their relationships, their work, their militancy, their reflections, their discussions, their actions, their words, their spirituality, their prayers.

1944-1947: the first priest-workers

In the mid-1940s (from 1944 onwards in France to be precise), a small handful of priest-workers (P.O. for short) appeared as a collective phenomenon. The first diocesan priest to become a P.O. was in Belgium in 1942. The years 1944-1947 (they are sometimes too quickly eclipsed) are the first act in the history of the P.O.

The P.O. has no founder

Nobody founded the worker-priests. Nobody planned or programmed them. They did not appear all of a sudden. They are an informal movement. They come together in different ways. Priest-workers are not an invention of the Catholic Church, they are an innovation in Catholicism. The 1940s, in the economic, political, social, cultural and religious context of the time, was a period of great missionary intensity, in the face of the growing awareness of the wall separating the Church from the popular masses of the time, following the considerable impact of the little book France, a mission country? published in September 1943, written by two YCW chaplains.

The first P.O. were to be one of the components of this missionary movement. They were not the only ones, which was a safeguard against self-reference. They were linked to ecclesial institutions (dioceses, the Paris Mission, the Mission of France, religious orders and institutes). Let me be clear: the Paris Mission included priests from various dioceses and priests sent by the Mission de France, not forgetting that lay people were also part of the Paris Mission from the time it was founded and launched by Cardinal Suhard in January 1944. In Paris that year, two diocesan priests from the provinces became P.O., and several others followed in the years that followed. The astonishing novelty of the existence of the P.O. raised many questions because it revolutionised the traditional image of the Catholic priest.

Ancel and Suhard

Alfred Ancel (auxiliary bishop of Lyon in 1947, at the age of 49) was sensitive to the initiatives taken by Cardinal Suhard, the bishop of the missionary renewal in Paris. In 1946, Ancel founded the Part-Dieu Mission in Lyon, with the aim of contributing to the evangelisation of the working-class world. He entrusted this mission to René Desgrand, a Prado priest who, quickly convinced that the working class had to be shared through work, was taken on in 1947. In 1949, he was joined by two other Prado priests who became P.O., Paul Guilbert and Jean Tarby. Ancel also helped Jean Fulchiron and René Margo to make the transition to work.

Ancel was concerned about improving the living conditions of working-class people. At the time of the great strikes of November-December 1947, he published a vigorous statement in the bulletin of the diocese of Lyon to draw the attention of Christians to the misery of the workers and the right to wage claims. At the same time, he was concerned that the Church should be able to make faith in Jesus Christ and the Christian life possible among these people. Ancel was certainly close to Suhard, who even considered asking him to be auxiliary bishop of Paris. Both were keenly aware of the wall separating the proletarian masses and the Church.

1948-1954: towards the end of the P.O. campaign

1947 was a pivotal year. 1948-1954 was another period that ended with the French P.O. ceasing operations on 1 January.er March 1954, by decision of the Vatican hierarchy. In a very complicated general situation, these years are delicate to look at closely, without waxing lyrical or ideological. There is an abundance of documents from the episcopate, the Vatican and the P.O., but the story is not limited to discussions and more or less tangled, incompatible or tumultuous relations between the P.O. and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, which would be a reductive, ideological and clerical view of our real history.

Letter from Ancel in June 1949

When Suhard died on 30 May 1949, Ancel sent Gerlier, his cardinal bishop in Lyon, an astonishing letter dated 2 June 1949, excerpted below: " You cannot be unaware of certain predictions being made about me, concerning Cardinal Suhard's succession (...). If you should ever learn that my name is being put forward, I would be grateful if you would make known to the Nunciature, before any more official steps are taken, certain objections that I believe, in all conscience, I should set out (...). " After highlighting his "personal shortcomings", Ancel went on to express his conviction that Antoine Chevrier's message was an opportunity for "spiritual renewal" for the Church. " If we had listened to Father Chevrier's message earlier, it seems to me that the barrier that now seems insurmountable would not have been established between the workers and the Church. Father Chevrier's mission dates back to 1856. It followed the Communist Party Manifesto by eight years. There are some obvious similarities (...). " Finally, after recalling his obligations to the Prado extension service, he revealed to Gerlier for the first time a very surprising project that was close to his heart : " ... I do hope that, in a few years' time, I'll be able to leave my place at Prado to others. At that time, I could ask the Sovereign Pontiff for permission to join our priests working in factories.. They would like to have a bishop with them. Of course, they are happy with the confidence shown in them by the hierarchy. But if they had a bishop with them, their fellow workers would understand better that they belong to the Church. By remaining auxiliary bishop of Lyon, I could, if I could live with them, mark the unity of the Church and its establishment in the proletariat. ". This letter from Ancel in 1949 is quite a programme! It contains everything that motivated and formed his path on earth (see the conclusion of this article).

Organisation of the P.O.

In 1949, on the initiative of the Paris Mission, the P.O.s (of which there were several dozen) organised their first national meeting; they set up an informal secretariat and decided to meet regularly at national level twice a year. Between 1950 and 1954, there were 7 or 8 national meetings. In 1951, at a national meeting in Lyon, the P.O. organised itself like a trade union (explicitly referring to a "national secretariat" and an "executive commission"); a national secretariat was therefore elected, from which this or that P.O. was deliberately excluded. This position vis-à-vis the episcopate probably complicated matters in the context of an already difficult situation where suspicions, calumnies, denunciations, misunderstandings and warnings were piling up against the P.O.. In a situation that was becoming increasingly alarmist and critical, it was not easy to live the necessary and fruitful tension between innovation and institution.

However, during the years 1948-1954, it must be honestly and objectively acknowledged that there were differences between the P.O.s themselves (before 1954, there were around 130 of them) in the way they saw their presence, work, commitment and mission in the working class and the proletarian masses. Questions of leadership have also arisen, and differences have become more pronounced and more fundamental, with tensions that are very difficult to reconcile. These profound differences between the P.O.'s were often overshadowed by their common resistance, their solidarity, in the face of misunderstandings and mistrust from the hierarchy or injunctions from the Vatican. Perhaps also, the spiritual dimensions of this new style of priestly existence were more or less eclipsed by the hold of temporal and theological ideologies.

A complicated relationship with the P.O.

In this context, Ancel's relationship with the worker-priests was to be complex. However, he was very concerned about the question of evangelising the working class (see his brochure published in 1949 Evangelising the proletariatIn 1950, Ancel was a member of the Episcopal Commission for the Working World. It seemed to him that the P.O. were heading in the wrong direction, in particular because of the influence of the priest's temporal involvement in the workers' movement. In agreement with the bishops who had P.O.s in their dioceses, he envisaged a project for a Directory to guide the activity of the P.O.s. In 1950-1951, as this matter of the Directory had given rise to numerous reactions and discussions on various sides, this controversial project, as it was formulated, had no chance of succeeding given the atmosphere of the time. Criticised, disowned, finding himself in a way disqualified, not wanting to get in the way, Ancel took a back seat at national and local level, without losing interest in the P.O. In fact, he continued to think about the usefulness of priests working as workers, even envisaging " ask the Sovereign Pontiff for permission to join our priests working in factories "as he wrote in his surprising letter of June 1949.

Letter from Ancel in August 1953

A letter addressed to Cardinal Gerlier on 12 August 1953, concerning the foundation of a " mission ouvrière du Prado "(later referred to more modestly as " a pradosian community in a working-class neighbourhood ") reveals how Ancel envisaged the realisation of the project that had been maturing within him since 1949. " ...I feel that I don't have the right, in good conscience, to allow Prado priests to enter the working world if I don't go with them. I would have the impression of being like a vicar apostolic in the Far East who wanted to direct his priests while staying in Paris... My contacts with the A.C.O. and with the workers' parishes, my membership of the episcopate and the relations I have had with the workers' priests, my doctrinal training and my social studies on the working class condition and Marxism, seem to me to offer some guarantees for a ministry that will be extremely difficult if it wants to be, at the same time, fully faithful to the Church and truly present to the working class world... I feel drawn, in a constant and almost invincible way, towards poverty and towards the poor. Admittedly, I have failed more than once to be faithful to this attraction, but I am continually drawn back to it. It's stronger than I am. I feel very strongly that I wouldn't be at peace if I took a decision that prevented me from being faithful to him... " At the time Ancel wrote this letter, the prospect of the P.O. being discontinued by decision of the hierarchy was becoming increasingly clear.

The shock of 1er March 1954

The 1er March 1954 was the final date when the French P.O.s were stopped, a decision taken by the Vatican and implemented by the French episcopate. The Belgian P.O. stopped at the end of July 1955, when there were 8 of them. The French P.O. were faced with an impossible choice, a crucial decision: leave work and stay in the Church or stay at work and leave the Church. Some P.O. hesitated a great deal, others changed their position in the days, weeks or months that followed. There were around 85-90 of them on the eve of 1er March, including 5 pradosians. Some P.O. had quit before or were not directly concerned by the ultimatum. Around forty P.O. decided to leave work temporarily and remain in the Church. From 1954, they gradually committed themselves to defending this style of priestly life, and, in agreement with their bishops, they gradually returned to working-class jobs, taking more or less into account the restrictive conditions set by the hierarchy for working. Around fifty P.O. decided to stay at work and leave the Church. Among them, several left the working class to pursue professional careers more suited to their education, culture and abilities; they married a girlfriend more or less quickly or later. About twenty others, several of whom remained single, continued their commitment to the working class and the labour movement.

1954-1965: the hope of a revival for the P.O.

The story did not end in 1954 or 1959. The revival of the P.O. in 1965 didn't happen all of a sudden, it didn't fall from the sky. After the decision taken by the Catholic hierarchy to stop the P.O. on 1er March 1954, there was a new blow from Rome in July 1959. At that time, not many people believed in a possible future for this form of priestly existence initiated by a handful of P.O.s in France and Belgium in the 1940s.

Ancel and the Gerland period (1954-1959)

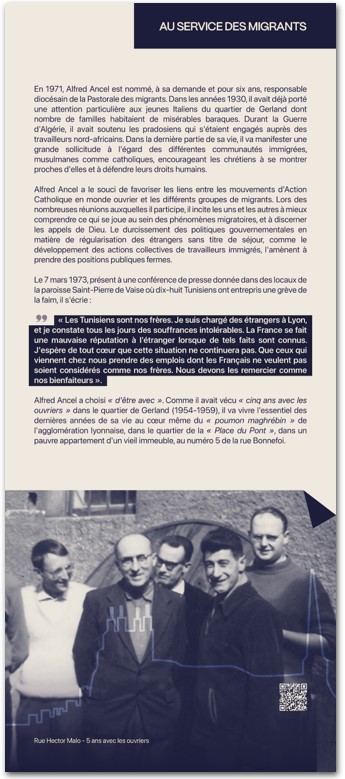

In these very unfavourable circumstances, Ancel nevertheless went ahead with the astonishing project, which he had been carrying deep inside him since 1949, of going himself to live in a certain way in the working class condition. After requesting and obtaining "permission" from the Vatican on 15 June 1954, Ancel, together with four other members of Prado (consecrated lay people and priests), set up a small Prado community in the working-class district of Gerland in Lyon, which included living close to the proletariat and sharing the working-class condition through work, since he himself worked as a home-based labourer. This unprecedented community lasted until July 1959, when it was again banned by the Vatican. Despite the limitations of this experiment, it was still a totally unprecedented type of episcopate! And perhaps also a small sign of hope.

On several occasions, Ancel has testified to the great spiritual intensity he experienced during this period at Gerland. In 1959, when he had to comply with the Vatican's decision to cease this experience (letter of 27 July 1959 to Cardinal Ottaviani, one of the pillars of the Vatican) : "I think I can say that this five-year period has been one of the most fruitful of my ministry".. In 1963 (in the book Cinq ans avec les ouvriers p.364) : "I can admit that I learnt more spiritually during the five years I spent at Gerland than during the rest of my priestly life. In 1972 (at the time of the 25e anniversary of his episcopal ordination) : "I especially remember the years I spent in Gerland, among the workers, trying to share something of the working class condition myself. I think those years were the richest and most fruitful of my episcopate, both spiritually and apostolically... It was there that I felt more like a bishop and successor of the Apostles". The end of this working-class experience in 1959 was certainly a profound spiritual test for Alfred Ancel, in his unshakeable attachment to the Church, a trying spiritual uprooting that emptied him of himself. You could say that true spiritual life is physical!

The 1959 stoppage

The decision of the P.O. on 1 March 1954 was mainly a disciplinary measure taken by the episcopal hierarchy, whereas the decision of July 1959 was more of a doctrinal measure. On 3 July 1959, a letter from the Holy Office (the Vatican's doctrinal office) was sent to Archbishop Feltin of Paris, President of the Workers' Mission, and to Bishop Liénart of Lille, President of the Assembly of Cardinals and Archbishops. This internal document was published in Le Monde (15 September 1959) and in La Croix (16 September 1959). In the form of a doctrinal statement, this letter forbade priests to engage in any salaried professional activity, which signified the incompatibility between the priesthood and working-class life, between the life of a priest and the working-class condition.

However, this ban will remain largely ineffective, as if the Vatican had contented itself with a declaration of principle. It was as if the Vatican had said: we'll ban it, but we'll leave it alone, we'll get round the ban, we'll see what happens. In fact, the P.O. who found work after 1954 never left. On the other hand, without being disowned, a significant number of priests took up paid employment, discreetly and often on a part-time basis. They saw their work as a means of being present, of being close to people and of apostolate in the working world. However, the unresolved question was that of full-time work, the life of a worker, sharing in the working class condition, the possibility of involvement in the trade union movement, social struggles, liberation movements, a temporal commitment that constituted the main complication and confusion between the Catholic hierarchy and the P.O.'s.

P.O. initiatives

The P.O. who remained at work on 1er In March 1954 (there were about fifty of them), they considered and declared themselves to be at odds with the Church institution. From 1957 onwards, some of them took the initiative to form a group made up of P.O.s, most of whom remained single, committed to the working class, manual labour, trade unionism and fidelity to a militant working class life on a daily basis. From 1957 to 1965, they organised national meetings, with a variable number of participants (from 10 to 20), to which they sometimes invited one or other member of the institutional Church. In June 1964, fifteen of them wrote a long "Letter to the Fathers of the Council". Later, these P.O. would be referred to or would define themselves as "insubordinate", while the others did not call themselves "submissive". For a variety of reasons in different circles, the term "insubordinate" began to gain currency in the 1980s.

Several of the P.O. who left work temporarily on 1er March 1954 did not submit to the disciplinary decision of the hierarchy, but accepted it. During the years 1954-1965, their tenacity kept alive the hope of a revival, amplified by the prospect of a Council. Very quickly, most of them got together, with a few bishops, to undertake a rehabilitation of this way of living the priesthood and to envisage delegations to Rome. Most of them quickly found work in small or medium-sized companies, with the agreement of their bishop. They made several delegations to Rome, and one was finally received by John XXIII in February 1960. By the end of 1964, there were around forty P.O., most of them from the first generation before 1954. In order to respect the real story and avoid a tendentious, romantic or ideological interpretation, it would be preferable to say the insubordinate within the Church and the insubordinate outside the Church.

The Second Vatican Council

In the Catholic Church, this period was obviously marked by the major event of the Second Vatican Council (opened on 11 October 1962; closed on 8 December 1965). On 25 January 1959, John XXIII, who had been elected Pope three months earlier, announced his intention to convene a Council in front of an audience of stunned cardinals. Without considering France as the centre of the world, we should draw a connection between John XXIII's intention and the fact that he had been the Vatican's representative in France, in Paris, from the end of 1944 to 1953, where he witnessed everything that was being sought at apostolic level, even if he was very reserved about the P.O. We should also mention the considerable impact of John XXIII's encyclical "Peace on Earth", in 1963.

On 23 October 1965, during the last session of the Second Vatican Council, the French episcopate, meeting in Rome in plenary session, " proposes, with the agreement of the Holy See, to authorise a small number of priests to work full-time in factories and on building sites, after appropriate preparation. This authorisation for salaried manual work, currently very limited in number, is planned for an initial period of three years... This initiative will be the responsibility of the Episcopal Committee for the Workers' Mission, which is empowered, on behalf of the episcopate, to monitor this first stage. ". On 7 December 1965, on the eve of the close of the Second Vatican Council, the decree on the ministry and life of priests was promulgated. This decree (chapter 2, paragraph 8) lists the various functions of priests as follows those who work manually and share the working class condition ".

Ancel and the Second Vatican Council

Alfred Ancel certainly invested a great deal of himself, in a humble and determined way, in the work of the Second Vatican Council. In 1964, he was elected president of the Episcopal Commission for the Working World (he had been a member since 1950) and a member of the Select Episcopal Committee of Bishops for the Workers' Mission (an institution founded in 1957). It was in this capacity that he wrote notes on the work of priests. Following the vicissitudes of a Directory for the P.O. (1950-1951), which was finally abandoned, Ancel humbly withdrew from the P.O. collective, while continuing to believe in this form of priestly existence.

At the decisive moment when the French episcopate relaunched the P.O. (1964-1965), we can think that Alfred Ancel, in a discreet way, was probably one of the key players. What's more, like other bishops at the Council, he was also motivated by the vision of a Church that served the poor (see his brochure The Church and poverty published in 1964). Despite his strong reservations about the temporal commitment of priests, Ancel did not question the fact of working-class priests. In a 1978 letter, he set out, in a more nuanced and favourable way, what had become of his thinking on the involvement of priests in the workers' movement.

1966-1974: a new boom for the P.O.

1966-1967-1968 was "an initial period of three years" for the passage of priests into the world of work, in accordance with the decision of the French episcopate. Direct responsibility for this start-up was entrusted to a "Restricted Team" appointed by the Episcopal Committee for the Workers' Mission. This team is made up of five priest members (an official animator; a P.O. from the 1940s and from the Paris Mission; the general secretary of the Mission ouvrière; a person in charge of the Mission de France; a representative of the institutes and religious orders).

Getting started at work

In 1966, the list of priests authorised to work as workers was drawn up diocese by diocese, according to criteria established by the Mission ouvrière. In this official list, there were 52 names, including one P.O. from before 1954, and among them 8 priests from Prado. They were divided into about fifteen teams. Many of the 52 candidates had already been involved in working life in various ways. For this first sending, there were more volunteers than the limited number foreseen, which generated some frustration.

On 4 October 1966, a final preparation session was held for these priests at the adult vocations seminary in Morsang-sur-Orge. Ancel was asked to lead the spiritual retreat. He began as follows: " I would like to express my joy at seeing you gathered here. We have suffered a great deal, all of us who, in the past, have had to stop our work; but it is a joy for us and an immense hope to see that what was started yesterday will continue tomorrow. No doubt the manner will not be the same, but the profound impetus is the same. Through our priestly presence in the midst of the working world, we want to show them in a concrete way that the whole Church, with its laity and priests, is with them. We also want to bring them the message of Christ, certainly in its entirety, but in such a way that they can understand and accept it. The presence of a sign, the presence of evangelisation, that's what the first priest-workers wanted, and that's what you want too, you who are about to go to work. The second wave follows the first; it's the same flow. "

Mission Ouvrière and the P.O.

At the end of 1965, the hierarchical decision to make it possible for priests to return to work in the factory was a rather surprising event for the Church, which did not believe in it. However, as soon as the new teams of "priests at work" were set up, from 1966 to 1968, reactions were diverse and long-lasting. In the P.O. milieu, some were more sensitive to the hierarchical decision to "take over", others to the conditions of this "take-over" ("compromises" for some). On the other hand, some felt more than others that they were under the tutelage of Mission ouvrière; quite quickly too, the new teams found themselves cramped by the established arrangements. Even if the main thing had been achieved (being able to work as a worker), the systems put in place could appear, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the location, to be more supervision than support. Clarification came gradually, accelerated by the events of 1968. "Priests at work" was the official name adopted by the hierarchy, but elsewhere the term "worker-priests" continued to be used.

Despite an agreement drawn up on 30 May 1966 between Mission ouvrière and Mission de France, the episcopal decision to entrust Mission ouvrière with the task led to more or less muted tensions between these two Church institutions, between the P.O.s themselves, and also to an internal crisis in Mission de France in 1969 with the resignation of its Central Team. In 2014, in the press kit presented to mark the 60th anniversary of the Apostolic Constitution given by Pope Pius XII to this Church institution (1erAugust 1954), the Mission de France itself reports this internal crisis as follows: " 1965: Pope Paul VI authorises the resumption of priest-workers in a context of conflict between Mission Ouvrière and Mission de France. 1969: The Council of the Mission de France resigned. It felt that its pre-eminent role as a missionary instrument of the Church in France was not being heard by the episcopate. "

The upheavals of 1968

Then came the shock wave of social unrest in the spring of 1968 (notably the "Workers' May"). That year, at Pentecost 1968, it was planned to take stock of the first three years, but in view of the events, it was postponed until All Saints' Day. This national meeting brought together in a single collective the former P.O. teams who were rebellious in the Church (those who had left work on 1er March 1954 and had subsequently returned to salaried employment in agreement with their respective bishops) and the new teams sent out in 1966. At the end of the meeting, eight P.O. delegates were elected to the new "Équipe Nationale des Prêtres-Ouvriers" (E.N.P.O. for short).

During the years 1969-1973, the E.N.P.O. moved towards an autonomous team made up of P.O.s elected by the regions (one per region or particular group). In 1971, a Synod of Bishops was held in Rome, with two main themes: the ministerial priesthood and justice in the world; the E.N.P.O. sent a contribution that was published by Mission ouvrière: " Priest-workers, what they experience, what they think of the ministerial priesthood ". In 1973, the E.N.P.O., while still linked to and present at various Church bodies in France, was constituted, for practical reasons, as an Association under the Law of 1901 (J.O. of 8-9 October 1973), the canonical status of each P.O. remaining that of priest of a diocese or priest of the Mission of France or member of a religious order or institute. Then, in 1974, for the first time, the E.N.P.O. elected a P.O. as secretary, recognised as such by the ecclesiastical authorities.

In the very specific context of the post-1968 period, which was critical of the institutions, various currents ran through the French clergy and many priests left the ministry. The years 1969-1974 saw the arrival of new P.O.s, more and more of them over the years, and at the same time a widening of the geographical spread (in the regions, most of the départements, small and medium-sized towns and rural areas). They linked up with the E.N.P.O., whose primary concern was not the social status of the clergy or the institutional transformation of the Church. Almost all the P.O. were involved in trade unionism, either with the CGT or the CFDT. In 1974, there were about 750 P.O. in France, including about sixty Pradosians. Then, from about 1975 to 1985, the P.O. movement reached its peak (there were a lot of us back then, and we were in great shape!), and it was also a period when it seemed right not to become "a separate priestly body" in the Church, as the saying went at the time. To a lesser extent, the P.O. movement developed in Belgium, Italy and Spain.

Ancel after the Second Vatican Council

After Vatican II, Alfred Ancel continued to chair the Commission épiscopale du monde ouvrier (CEMO), and was re-elected chairman in 1967. He was also one of the five bishops who made up the Comité épiscopal de la mission ouvrière (the CEMO), which on 29 June 1965 signed the editorial of an important document at the time, the priesthood in the workers' mission, drawn up by the Secrétariat National de la Mission Ouvrière. On 27 October 1968, Ancel and Marius Maziers co-signed a Letter to Catholics in France from the bishops of the Commission du monde ouvrier and the Comité de la mission ouvrière. In 1972, it was a " CEMO's reflections in its dialogue with Christian activists who have chosen the socialist option ".

In 1971, Alfred Ancel became involved in the Pastorale des Migrants. In the 1930s, he had already paid particular attention to the Italian families living in miserable shacks in the Gerland district. In the latter part of his astonishing career, he showed great concern for the various immigrant communities. At the many meetings he attended, he encouraged participants to better understand what was at stake in the migratory phenomenon. In the last years of his life, he was present in the Maghreb community of the Place du Pont district, living in a poor flat in an old building.

At the time of Alfred Ancel's death on 11 September 1984, Henri Krasucki, General Secretary of the CGT at the time, wrote to Cardinal Decourtray, Archbishop of Lyon: " I know that in him, the man of the Church merged with his thoughts and actions. I respect this truth. I have long known and admired his life story, his understanding of the world, of the humble and the oppressed. His understanding of the world of work as it is and of the workers' movement is particularly close to my heart, without reducing the scope of his work and his vision of humanity [...] He was a pioneer of great stature, opening up paths that I am convinced have a great future. "(telegram, 13 September 1984).

Ancel's trajectory has been faithful to his astonishing letter of 1949 (see the beginning of this article). This letter was like a roadmap, in particular by making a bold comparison between Antoine Chevrier's conversion-mission at Christmas 1856 and the publication in 1848 of the Manifesto of the Communist Party (at that time, there was no political party so called). Ancel's letter reveals : 1- his desire to live himself as a bishop in the working-class condition (which he would achieve in a way from 1954 to 1959), without the pretension of being a "working-class bishop"; 2- his conviction that the existence and charism of Antoine Chevrier, founder of Prado, is an opportunity for the spiritual renewal of the Church, a free gift in favour of the whole Church ; 3- his attention to social issues, his presence among the poor, his interest in the study of Marxism, his open dialogue with Communist militants and leaders; 4- his unwavering commitment, based on an intense spiritual life, to a Church open to the poor.

What will be the future of all this?

Alfred Ancel died in September 1984, five years before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. The following years saw the break-up of the USSR and the collapse of the communist systems in Eastern Europe. One might therefore think that Ancel's objectives were outdated. On the other hand, the heyday of the priest-workers dates back half a century (1975-1985). The world and societies have changed considerably, it's obvious, it's not over, and we have to expect the unexpected! The history of Mission Ouvrière and the P.O. - like that of the Catholic Church - is not perfect. But we mustn't forget or disdain the spiritual, Christ-like, liberating dimension that has animated the missionary concerns of these early periods since the 1940s.

Today, as in the past, many people are exploited, oppressed, excluded, despised, mistreated and forgotten. The powerful, the owners and their empires continue to impose their system of domination. There will always be a need for liberation movements. Gustavo Gutiérrez, who passed into eternity on 22 October 2024, comes to mind. He is recognised as "the father of liberation theology", which he promoted as a liberating spirituality, far more revolutionary than progressive theologies. The history and existence of the Workers' Mission and the worker-priests can be seen as one of the signs of the mystery of God Incarnate, which extends beyond the Churches. Christianity can thus be seen as a kind or style of life (this is even the title of a book by Christoph Theobald: Christianity as style) and an insurrection-resurrection of the human being. We can also see human development as a very important religious, theological and spiritual issue. There will always be a call, despite the forces to the contrary, to serve human development, to bring life to birth and rebirth, to be co-creators of a good and kind world in the wake of the splendid poem of the seven-day creation, which opens the mythical account of origins (Genesis ch. 1 to 11) and the whole Bible, by adopting the style of Jesus and being breathed by his spirit. Quite a programme!

15 January 2025 – Francis GAYRAL, retired priest-worker

If you notice any significant errors or omissions, please report them to the editor of this article, who will be pleased to receive them.

Sources concerning Alfred Ancel