Major projects

Extract (pages 110-112) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

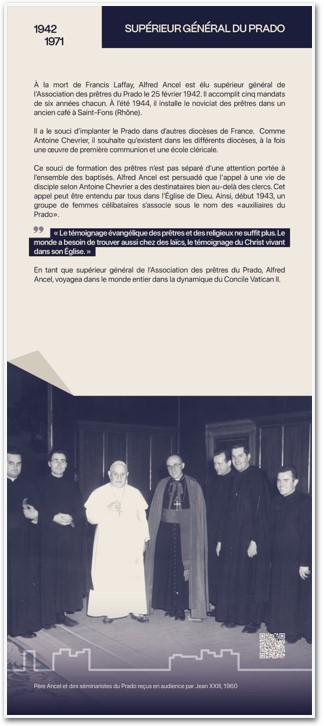

After Francis Laffay's death on 15 February 1942, a successor had to be found. On 25 February, the 54 electors convened by Paul Chervier met and Alfred Ancel was elected. He was to serve five successive six-year terms at the head of Prado, remaining its superior until 1971. It's enough to say that his history would become intertwined with that of Prado for almost thirty years. There is no question here of retracing that history. We will simply try, on the basis of the projects he set up and the guidelines he gave, to understand how Alfred Ancel experienced his ministry in the service of the Church as a spiritual battle. To do this, we will confine ourselves essentially to the period before his life at Gerland, i.e. up to the early 1950s.

When his brother Henri asked him one day if he ever regretted not having managed his father's business, Alfred replied: "Oh no! You see, for me, a factory is too small...". While this quip was humorous, as Father Ancel's remarks sometimes were, it must surely be seen as a completely sincere admission. If a business owner wants to prosper, he has to make plans and constantly come up with new projects. Were those of Alfred Ancel, who became superior of the Prado, at least by analogy, indicative of a great human ambition? As for the figures, they were remarkable. To give just two examples, the number of seminarians involved with Prado had risen from around thirty in 1945 to 195 by 1948; and while there were only 67 priests registered with the Society when Father Ancel took over from Father Laffay, there were already 442 in 1954. Many of the letters sent to the bishops when Prado began to leave the diocese of Lyon sounded like victory bulletins. It is true that at the same time, especially after the war, the Little Brothers and Little Sisters of Jesus and the Country Missionary Brothers, among other similar institutions, also developed significantly. But for the secular clergy, even taking into account the creation of the Mission of France by the Assembly of Cardinals and Archbishops in 1941, there was no comparable thrust to that of Prado.

Although impressive, were these results, which corresponded to the needs of the time in a France where the problem of adapting the Church to post-war society required bold innovations, commensurate with the ambitions? In the summer of 1944, Father Ancel announced to his confreres that the Fathers' Novitiate would be moving to Saint-Fons, alongside the N7, in the premises of a former café. Then he confided in them: "Shall I tell you what I really think? The future will show whether it is in line with God's will. It seems to me that, to really establish Prado in the different dioceses, there should be both a work of first communion (or a similar work) and a clerical school in each one. The work of first communion will keep us at the service of the poor, the humble, the underprivileged and sinners; the clerical school will constantly and vividly repeat the priestly ideal of Father Chevrier. Then the pradosian communities will be really solid: they will be founded on the same basis that Father Chevrier had established in Lyon (...). This is an anticipation, rather an intention of prayer".

To understand such projects, it is necessary to place them in the perspective of their creator. Prado, founded by Antoine Chevrier as a "Providence" for the education of adolescents deprived of a minimum of religious instruction and as a nursery for poor apostles, was destined to undergo considerable change. It was to undergo considerable change. We can speak of the veritable "mutation" of an institution, initially embodied in the "works" of Lyon, which was increasingly to become part of a social transformation and a missionary dynamism that affected the whole of the Church in France.

Serving a multi-faceted vocation

What, then, for Alfred Ancel, was the originality of the "pradosian vocation" in the great missionary decades of the post-war period?

When we look not at his projects, but at the directions he has taken, one thing is strikingly constant: this man has fought against 'Methodism' all his life. He himself uses this term, referring to a state of mind which, of course, has nothing to do with the Christian denomination that bears that name. For him, it is a "missionary deviation", and he gives some very precise applications:

"One of the signs that you have methodism is the amount of time you spend thinking about your methods. If a priest no longer has time to pray, to say his breviary properly, to look after his parishioners because he has to think about his methods, there's no doubt about it, the diagnosis has been made. He is methodist. Another sign of methodism is authoritarianism in the use of one method and exclusivism with regard to other methods. When a priest gets so caught up in the liturgy of the Mass in front of the people that he can't say it any other way, he's surely got it. When a priest is so caught up in his neighbourhood meetings and his Catholic Action activists that he can no longer see or accept anything from the outside, that's it: he's got it (...). Methods are servants, you have to use them and never be enslaved to them (...). No method is necessary, no method is universal".

Does this mean that Alfred Ancel doesn't care about methods in apostolic work and advises a disdainful relativism? Nothing of the sort. It is sectarianism that he is fighting: "Let us never allow ourselves to be taken in by theories which undoubtedly contain excellent elements, but which become false as soon as they manifest totalitarian, exclusive or sectarian pretensions. Let us do God's work well, and God will do his work.

This post was written in 1951. But back in 1926, in his homily on Saint John the Baptist in the Prado chapel, Alfred Ancel said: "You can see the relative importance to be given to the various apostolic works...". On this point, he was unwavering. Experience and circumstances could well modify his field of application and refine his vocabulary. His spiritual convictions remain. For example, at a time when holiday camps were flourishing and constituting the preferred ground for seminarians' apostolic activities, Father Ancel wrote to them: "It is not acceptable for a seminarian to spend several hours preparing for a rally or a small war and to improvise an explanation of the Mass! When all the priests and nuns were attending the Pastoral Congresses, he made his thoughts clear: "Through our Pradosian training, we know the essentials of the priestly apostolate, but that does not mean we should scorn the various methods and techniques adapted to today's needs (...). Those who, under the pretext of fidelity to the Gospel spirit, would despise modern techniques and methods, would show that they do not really possess this spirit and they would risk, by a necessary backlash, making people despise the Gospel spirit".

"Indefinitely", as he put it, he returned to Antoine Chevrier's parable about "the artificial tree and the natural tree", commenting: "No doubt you have to prepare the meetings, but you have to prepare the priest more than you have to prepare the meetings...". And one day, but this was in 1947, he invented another parable himself:

"To caricature a little, we could compose the prayer of the neo-pharisees as follows: My God, I thank you that I am not like other Christians, formalist and sclerotic, nor even like the Pope and the bishops who are still concerned about Christian schools and other outdated things... As far as I'm concerned, I live like a poor man and I am incarnated in the masses, I am a living witness and I'm not worried about rules, the spirit is enough for me." And he quotes an old story: "It is said that a Russian (he must have been a perfect revolutionary), noticing that his trousers were dirty and torn, with a vengeful gesture, threw them into the fire... and afterwards, he realised that he didn't have another pair. The story is certainly not true, but what it means has been done more than once."

This call could be heard by everyone in the Church of God

As we can see, these evangelical orientations were essentially addressed to priests. However, Alfred Ancel was fully convinced that the call to a life of "discipleship", of which Antoine Chevrier had been a bare but luminous witness, was addressed to people far beyond clerics alone. As he would later affirm in his last book, this call could be heard by everyone in the Church of God: bishops and priests, religious men and women, lay Christians... But it was above all the latter that he had in mind at the time: "I say it again today: the evangelical witness of priests and religious is no longer enough. The world needs lay people to bear witness to Christ living in his Church. In fact, the religious situation in our country, and not just in the working classes, has deteriorated even further over the last century (...). Without doubt, there are still vestiges of Christianity in our country: we know this from surveys on faith and religious practice. But these undeniable facts should not blind us to another reality: that of the gradual disappearance of the faith and even of the Christian humus in increasingly large sections of the French population, especially among young people (...). In a way, our times demand that lay people commit themselves, while remaining lay people, to the ways of evangelical perfection. Our world needs to see a sufficiently large number of lay Christians sharing with everyone the life of marriage, professional work and earthly commitments, living truly according to the spirit of the Beatitudes and manifesting Jesus Christ through their whole lives."