Bishop Ancel's interventions at the Council

Extract (pages 217-220) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

(Mgr Alfred Ancel is) haunted by the apostolic desire to enter into dialogue with non-Christians...

His written statement of 26 November 1963 is very significant in this respect:

"In our text (on ecumenism) what is said about non-Christians, apart from the Jews, is very brief. Six very general lines are devoted to them, even though there are two billion of them in the world. What's more, human relations between Catholics and non-Christians are becoming more important by the day, even in regions that were once essentially Christian...".

Father Ancel went on to say that there was no question of falling into indifferentism, because we offend the truth by regarding all opinions as equally valid. Then he had a long paragraph on the respect due to non-Christian religions. In this, he broke new ground in relation to the pre-Conciliar schemas: seventeen had been retained, but none dealt with this vast question. Then Father Ancel, citing a report by Mgr de Smedt, Bishop of Bruges, which had made a strong impression, asked that the necessary dialogue with non-believers be dealt with seriously: "I found several atheists who did not really reject God or true religion, but only false concepts about God or counter-testimonies from certain Christians that we too must reject. I've even known people whose way of life helped me to become a better Christian. It was certainly a gift from God in them (...). One atheist communist said to me: "If you want us to believe in the spiritual, you have to prove it to us through your life. And another: "What I reproach you Christians for is not being Christian, but not being Christian enough" (...) The title of this outline could be kept as it is, provided that a distinction is made between ecumenism proper and ecumenism in the broad sense...".

This "distinction", whatever its author wanted to think of it, was a confusion in the sense that it obscured the first and original meaning of the term and risked maintaining the ambiguity. This is a point that can be pointed out as a certain limitation in someone who, unlike many other Council Fathers who were less sure of themselves in theology, hardly ever called on this or that "expert" to write his personal interventions. Nevertheless, his testimony on dialogue with unbelievers and the emphasis placed in his text on respect for believers of other religions were a very positive contribution which would help, among other things, to advance the project of autonomous Declarations on "non-Christian religions" on the one hand and "religious freedom on the other".

At the end of the first session, Mgr Ancel was, along with Mgr Guerry and Mgr Huyghe, Bishop of Arras, one of eleven French bishops to speak publicly on the subject of the Church. But while the first of them to speak on this theme, Cardinal Liénart, had insisted on a theology of the Church as Mystery, and Mgr Guerry had begun the fundamental reflection of the Council on episcopal collegiality, Mgr Ancel's speech, summed up by one of the best chroniclers of the conference, might at first sight seem rather simplistic: "For Mgr Ancel, the antinomies between authority and freedom, primacy and collegiality, legalism and spirit will be resolved by a return to the Gospel. It is not enough to say that the opposition is merely apparent, or that the realities are complementary. The Church's charter is set out in the Gospel (...) We must not, therefore, set a community of love against a juridical society, but strip the juridical element of that which risks disfiguring, in the eyes of believers or non-believers, the true face of the Church".

Simplistic? In truth, in this speech, made on the eve of the closing of the first session, Archbishop Ancel's first intention was to support the speech that Cardinal Lercaro, Archbishop of Bologna, had made the previous day. The Cardinal had spoken at length about poverty as a sign of the Incarnation, and the evangelisation of the poor as a sign of the Kingdom. He had been less interested in the earlier speech by Cardinal Montini, Archbishop of Milan, who had masterfully highlighted the theme of the Church inhabited by Christ and communicating him to the world as the "central argument" of the Council. Archbishop Ancel insisted that the evangelical sources of the Church should be better shown, because this would, he said, allow the exercise of power within the Church to be better founded as a humble service. And he concluded:

"It is not in vain that the Holy Gospel is solemnly expounded in the aula of the Council every day. It is not enough to consider it only as a book of spirituality, nor as the simple illustration of dogmatic theses: it is rather as the very source of doctrine that we must welcome it, because in truth it is.

During the second session, Bishop Ancel addressed the Assembly only three times, but when he spoke on 24 October 1963, he did so on behalf of five cardinals and sixty-five French bishops. Once again, the amendment (presented in chapter six of the outline on the Church then under discussion) emphasised the evangelical foundation. But this time it was about the apostolate of the laity. At a time when the debate was dragging on, Mgr Ancel did not take a position on any of the major theological issues: the priesthood of the faithful or the problem of charisms, and so on. He gave a sort of homily to the Assembly in which, quoting more than twenty verses from the New Testament, he tried to show that the apostolate for the laity was not a contemporary innovation, since it had begun in the primitive communities.

In short, it was like a new chapter in "True Discipleship" applied to the laity... It is easy to understand, reading Father Ancel's countless pages in which the Gospel appears in every line, why he wrote the following to Father Haubtmann at Christmas 1964: "Personally, I am not an exegete, and I know that exegetes have some difficulty in admitting this use of the Bible (mine), but if exegetes must be called upon for the meaning of texts, I do not think that the use of Scripture is solely within their remit". However, for Alfred Ancel, as for Antoine Chevrier, "Scripture" meant above all the Gospels and the Pauline Epistles. For Mgr Ancel, the Acts of the Apostles had to be added. As for the Old Testament, he rarely referred to it. No doubt he did not draw much inspiration from it because he had not had access earlier to a comprehensive study of his 'main ideas', as Albert Gelin, who was a friend to him, liked to develop them at the Faculty of Theology of the Catholic Institute in Lyon?

Nevertheless, his speech on 24 October received the "approval of the lay listeners" who had just been admitted to the Council assemblies.

The mystery of the Church in its relationship with Christ, "Light of the Nations".

Extract (page 221) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

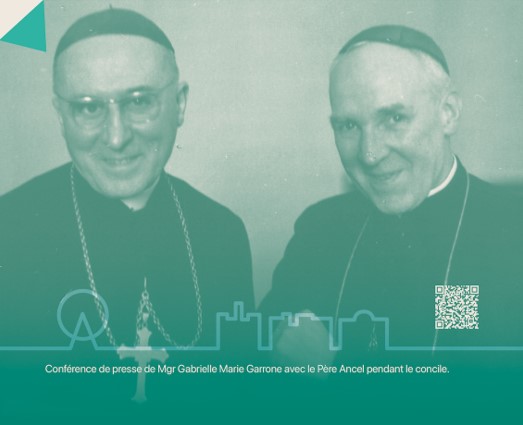

Although Bishop Ancel was less involved in the debate, he was by no means inactive. Before expressing himself twice, once in writing and once orally, on the central question of episcopal collegiality, he was one of those who tirelessly practised it. Just as at the first session, for example, he had taken part in the meetings organised between the French and Germans, so we see him passing through Florence before going to Rome in October 1963, in the company of Mgr Garrone, Mgr Marty and Mgr Veuillot. It was a meeting organised for an exchange with the Italian bishops, which was to have the best effect on the subsequent progress of the work. In addition, a very international group had been set up in 1962 around Cardinal Lercaro, Archbishop of Bologna, who was trying to raise awareness at the Council of the realities of the Third World and the demands of evangelical poverty in the Church.

Even before proposing his amendments on the question of collegiality, Bishop Ancel spoke on 2 October, shortly after Cardinal Gracias, about the Church in its relationship with the Kingdom of God. Antoine Wenger points out in his report that the speaker was "known to bishops all over the world because of his experience as a working bishop": "Faithful to the tendency he had shown at the first session, he would appear throughout the Council as a conciliator and moderator, inviting everyone to find positions where they could meet in authentic fidelity to the Gospel and in loyal openness to our times".

In fact, Mgr Ancel explicitly quoted Cardinal Florit, Archbishop of Florence, in his speech on 2 October. Again taking the Gospel as his starting point, he wanted to point out the "essential differences" to be found in the Church compared with earthly societies: "The Church has nothing to do with societies that are closed in on themselves or with a society that would like to dominate the various nations by its own strength. The Kingdom of God is a kingdom of peace which, through the power of the Holy Spirit, extends to the ends of the earth. This is why Christ said to his disciples: "Do not be afraid, little flock; it has pleased your Father to give you the Kingdom" (Luke 12:32).