Auxiliary for life

Extract (pages 139-141) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

On a cold winter's day, Father Joseph Ancel recounts how he met his brother Alfred by chance in the Place Bellecour. Alfred was coming unhurriedly from the rue Auguste Comte and, curiously, he looked "very sad":

- What's the matter with you?

- I can't believe it myself. Imagine that the Cardinal has summoned me to ask me, in the name of obedience, to become his auxiliary bishop. I'm counting on you to be discreet. But, you see, I'm overwhelmed.

- That's great news! I'd be delighted if a priest like you, who lives in the spirit of evangelical poverty of Prado, became a bishop... Don't you think the episcopate needs your witness?

- ....

Alfred Ancel was genuinely upset. His only desire was to remain at the service of Prado, which he saw growing rapidly. And it was because Cardinal Gerlier had assured him that he would let him continue his work as Superior that he could not refuse. In spite of himself, Father Ancel did not go unnoticed in the Church of France. The Archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Emmanuel Suhard, whose influence was so great at the time, had observed this modest member of the Lyonnais clergy. He told Cardinal Gerlier that he wanted him to become the titular bishop of a diocese. Feeling his own decline, Cardinal Suhard was looking for men who would continue the intense missionary work he had initiated. Alfred Ancel, with his evangelical training at Prado and his publications on working-class pastoral problems, seemed to him to be one such man.

Cardinal Gerlier understood his eminent colleague from Paris. But he also understood Alfred Ancel's inner choice. That's why he found the solution, accepted by Pius XII himself, of having him appointed to Lyon without taking him away from Prado. When he enthusiastically presented him to his diocesan colleagues on 24 February 1947, he wrote in the Semaine Religieuse: "This apostle of Jesus Christ, philosopher, theologian, sociologist, who aspires to realise in all his life the traits of the True Disciple, is first and foremost haunted by the sufferings of the popular masses, de-Christianised, abandoned, paganised (...). Should he abandon Prado, at the risk of compromising such a beneficial extension (...). The Sovereign Pontiff has deigned to keep Father Ancel at Prado, where he will remain, without refusing him the episcopate".

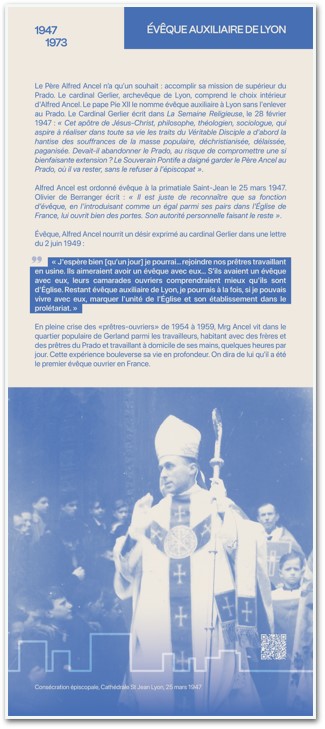

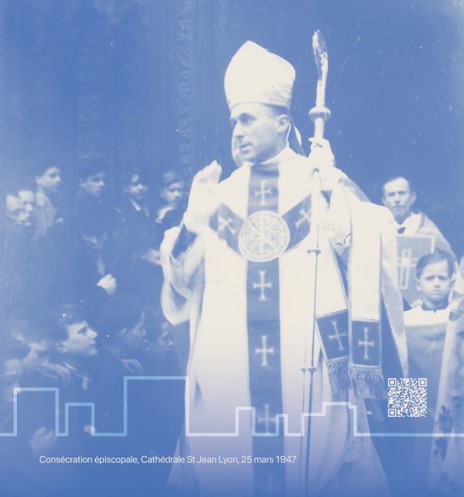

Cardinal Suhard, making the best of a bad situation, attended in person the consecration of the new bishop, which was celebrated in the primatial church of Saint-Jean on 25 March, the day he had chosen because, in the liturgical calendar, it is the feast of the Annunciation to Mary. Mgr Lebrun, Bishop of Autun, and Mgr Bornet assisted Cardinal Gerlier in the ordination rite. And three weeks later, Cardinal Suhard wrote to Mgr Ancel:

"Your Excellency and my dear Lord,

"Your letter of 12 April expresses the joy you felt at my presence at your episcopal consecration. I would like to tell you that I was the first to feel this joy myself. The satisfaction I felt from this consecration was not only the prospect of an Episcopate that is proving fruitful for the Church, but also the consecration of a work that seems to me to be increasingly useful and providentially prepared for the Catholic Church in our country of France.

"How, moreover, can we fail to admire the action of Providence, which made use of this man of God, Father Chevrier, to make him produce, even beyond his personal thoughts, all the ideals involved in the work of which he himself laid the first foundations? This work was to bring to the world the ideal of the holiness and poverty of Christ in the conquest of souls, and it so happens that today, through the formation of a clergy inspired by this thought, the idea is not only emerging, but is proving to be more and more assured and powerful...".

Reporting on the ceremony, the independent daily La Liberté concluded with a general sentiment: "The Church of Lyon can rejoice, it has the bishop it needs in the times we are living in".

The Prado was also jubilant. Aimé Suchet said simply, during the many toasts that followed the coronation meal: "What surprised us, moreover, was not that anyone had laid eyes on our Superior; his merits are too well known to us... but it was that the shelter he had voluntarily chosen by coming among us had proved ineffective".

[...]

Alfred Ancel was not the Bishop of Prado

[Alfred Ancel was not the 'bishop of Prado', whatever the confusion outside Lyon about this. But it is fair to say that his position as bishop, by introducing him as an equal among his peers in the Church of France, opened many doors for him. His personal authority did the rest, and this ordination on 25 March 1947 had repercussions on the history of Prado and, indirectly, on the evangelisation of the French working class world, which should be assessed. As for Bishop Ancel, he wanted to distinguish between his two very demanding roles, and one wonders where he found the time to accomplish so many tasks, from confirmations to countless conferences and meetings with the most diverse groups. His excellent health, his ability to fall asleep as soon as the night-light went out late at night, and his astonishing flexibility in moving from one job to another don't explain everything. He also had an aptitude for living in the presence of Christ, of whom he was aware, everywhere, of being a "representative".

The hypothesis that Mgr Ancel would leave Lyon to become the titular bishop of a large diocese was made more than once... by others than himself. The most serious alarm in this regard came shortly after his appointment, when Cardinal Suhard died on 30 May 1949. Among the names that had already been circulating since the beginning of Suhard's illness for his replacement in Paris, Alfred Ancel's name came up so insistently that Cardinal Gerlier thought it necessary to write to him:

"Eminence,

"You cannot be unaware of certain predictions being made about me concerning Cardinal Suhard's succession (...). If you should ever learn that my name is being put forward, I would be grateful if you would make known to the Nunciature, before any more official steps are taken, certain objections that I believe, in all conscience, I should set out (...)". Here, Father Ancel highlighted his "personal shortcomings". Then: "I am more and more convinced that Prado is a work of God, that Father Chevrier's message comes from on high and that the spiritual renewal he wished for according to the Gospel is a providential means that God has placed at the disposal of his Church so that it can better adapt to contemporary needs. If we had listened to Father Chevrier's message earlier, it seems to me that the barrier that now seems insurmountable would not have been established between the workers and the Church. Father Chevrier's mission dates back to 1856. It followed the Communist Party Manifesto by eight years. There are some obvious similarities (...).

Finally, after reminding the Cardinal that Prado was expanding rapidly and telling him that, in his opinion, no one was yet ready to succeed him, he revealed for the first time to his archbishop a project that he had nurtured within himself: "... I do hope that, in a few years' time, I will be able to leave my place at Prado to others. At that time, I could ask the Sovereign Pontiff for permission to join our priests working in factories. They would like to have a bishop with them. Of course, they are happy with the confidence shown in them by the hierarchy. But if they had a bishop with them, their fellow workers would understand better that they belong to the Church. By remaining auxiliary bishop of Lyon, if I could live with them, I could at the same time mark the unity of the Church and its establishment in the proletariat".

Alfred Ancel and Mgr Pierre-Marie Gerlier

The beginnings of Catholic Action and worker priests

Extract from the Blog www.enmanquedeglise.com - Article published on 1 January 2025 by Father Michel Durand.

The reading and study with Christoph Theoblad, followed by the video recordings with Cesare Baldi about his book L'Église c'est nous (The Church is Us), can only add to the reflections of the 'life review' type engendered by Goulven's work in interviewing me for the book: Michel Durand, un prêtre engagé entre fidélité et insoumission (Michel Durand, a committed priest between fidelity and insubordination).

It seems to me that I have always maintained that the Christian communities in parishes (local churches) were not missionary. I was told that, in fact, they were missionary, essentially missionary, and that my accusation did not hold water. But today I still observe and affirm the lack of missionary attitudes in the ordinary life of parishes. I see this in the parish of Saint-Maurice/Saint-Alban, the neighbourhood where I've been living for over ten years now. I know that saying this doesn't please the parishioners, so I try to explain myself, to argue; it seems to me that I can't really make myself heard. In short, doesn't this observation call for a kind of permanent review of life at the end of life?

If I had to go back to school to start a new life on earth, I would study pastoral theology, a practical theology that would make me open history books from the beginning of the 20th century. What did they say? What was the pastoral experience of meeting and evangelising people outside parishes before the 1914-18 war? I'm going back to the roots of Catholic Action.

While researching Alfred Ancel, auxiliary bishop of Lyon and superior of the Prado, I read a booklet published in 1987 by Editions Lyonnaises d'Art et d'Histoire, which deals with the life of Pierre-Marie Gerlier, archbishop of Lyon, 1880-1965. This appears to be a lecture given by Régis Ladous, Université Jean Moulin, Lyon III, on the occasion of an exhibition at the Musée de Fourvière on Pierre-Marie Gerlier. I've extracted a few pages from this talk that show the Church's missionary concern with the birth of Catholic Action. At a time when the Church in France (as I know it today) seems to be retreating into its sacristies, it seems important to me to revisit the history of the workers' mission, of the Priest-Workers (P.O.), of priests at work and of Catholic Action, in order to take a serious look at the Church's mission in this century.

Page 5

"In 1921, when Pierre-Marie Gerlier was ordained a priest in the prime of his life and after a long experience of lay life, he naturally thought of putting the talents he had displayed at the Palais to work for the Church: swapping the robe for the cassock, he would have liked to devote himself to preaching among the diocesan missionaries in Paris. Instead, his archbishop remembered that he had been a very effective president of the ACJF*, and immediately appointed him deputy director of works for the diocese. One episode stands out from his work in this position: the founding of the Jeunesse Ouvrière Chrétienne.

Gerlier only intervened at the end of the process, but in a decisive way. The YCW was officially launched in Belgium in 1925 by Father Joseph Cardijn. The following year, he was followed by Georges Guérin, who became vicar of Clichy. But the ACJF, with its rather bourgeois leadership, had no intention whatsoever of allowing itself to be dispossessed of the apostolate in working-class environments. At its national congress in 1927, it chose the apostolate to young workers as its theme. The risk was therefore that two rival organisations would emerge: a French YCW made up exclusively of young workers, based on the Belgian model; and a workers' branch of the ACJF, essentially controlled by the bourgeoisie. With the prospect of pontifical arbitration and an episode as unpleasant as the condemnation of Le Sillon in 1910 (Cf Michel Launay, Réflexion sur les origines de la J.O.C., in Mouvements de jeunesse, Paris 1985, pp. 224, 229, 230).

* Creation by Albert, de Mon de l'Action Catholique de la Jeunesse Française, 1886.

Page 11-12

"Another initiative, this time at the very heart of the Diocese of Lyon, was the pastoral revolution begun by Abbé Laurent Rémillieux in the new parish of Notre-Dame de Saint-Alban, in eastern Lyon: paraliturgies in French, Masses with dialogue, evening Masses, an altar facing "the people", the abolition of collections during services, the participation of lay people in pastoral life: what was called the "community parish". Here again, the initiative preceded Gerlier's arrival in Lyon and did not correspond to the cardinal's priority objectives. Here again, he discovered, he learned, and decided to support Rémillieux at a time when priests who were very involved in Catholic Action, and even in the YCW, such as Abbé Rodhain, considered Latin to be intangible, evening Mass to be unthinkable, the altar facing the people to be suspect and, generally speaking, any liturgical alteration to be sowing heresy. Not to mention the Roman Curia... In 1943, the creation of the Centre de Pastorale Liturgique in Lyon formalised a support that was all the more commendable given that Gerlier himself was far from sharing all the ideas of Rémillieux and his followers. As late as 1945, the cardinal, who was personally very cautious in this area, considered the celebration facing the people (the "upside-down mass") to be "an exceptional and limited method" (Jacques Gadille, Histoire des Diocèses, le diocèse de Lyon, op. cit., p. 297). It was this prudence which, generally speaking, saved a number of Lyon's initiatives from Roman condemnation and enabled them to succeed or develop".

Page 28

Saints go to Hell

The emergence of worker priests was preceded by a long prehistory that Émile Poulat has described in detail (Naissance des prêtres ouvriers, Paris, 1965); but it was the Second World War that enabled the project to come to fruition and become a reality. The Second World War led to the transfer to Germany of several hundred thousand French workers: volunteers, STO labour deportees and "transformed" workers (prisoners of war who had agreed to be transformed into "voluntary" workers).

From a religious point of view, this situation was compounded by a double refusal. Suhard and then Gerlier refused to grant special treatment to priests and seminarians affected by the STO: they had to share the same fate. The Nazi authorities refused to allow French workers in Germany to benefit from the spiritual and moral assistance of French chaplains. Suhard, followed by Gerlier, decided to break with a centuries-old tradition and authorise priests to carry out their priestly ministry underground, which of course meant that they were indistinguishable from the majority of French immigrants and had to work full-time in the Reich's factories, building sites and farms. In addition, in the prisoner of war and concentration camps, many priests also found themselves having to live out their priesthood in a complete break with the traditional model.

But it was not only within the borders of the Greater Reich that the war fostered ruptures and initiatives. France's defeat in a blitzkrieg led to an examination of conscience that revived the age-old theme of "France as a mission country", while completely renewing the traditional concept of the domestic mission. Once again, it was Suhard who was the pioneer, founding the Mission de France and then the Mission de Paris in the middle of the war. But Gerlier followed the movement and made a powerful contribution to its development thanks to his prestige, his organisational skills and his ability to mediate in difficult and conflictual situations.

For there was conflict; and the most extraordinary thing about this affair is that Gerlier should normally have been in the camp of the opponents of the worker priests. Indeed, the Mission de France and the Mission de Paris could be defined by a threefold break with the heavy-handedness of an "emparoissised" Catholic Action, with the Sulpician tradition of the priesthood, and with denominational organisations such as the CFTC. However, Gerlier remained very attached to Catholic Action, i.e. the collaboration between lay people and the hierarchy within the parish. He had been trained by the Gentlemen of Saint-Sulpice and remained throughout his life a supporter of priestly life in its most traditional form: it was thus that the 17th National Eucharistic Congress, which was held in Lyon in 1959, provided him with the opportunity to celebrate with great pomp the centenary of the death of the holy Curé d'Ars. He willingly recommended that Catholics get involved in Christian trade unionism, even though the conflict between the latter and the new missionary formula was so acute that the president of the CFTC, Gaston Tessier, went so far as to sue the workers' priests for defamation before the ecclesiastical court. All this did not prevent Gerlier from encouraging the appearance of worker priests in his diocese in 1946.

This open-mindedness undoubtedly stems from what Jean Guitton calls the gift of "second adolescence", the ability of exceptional people to renew themselves or welcome renewal when they have already reached an advanced age. But we can just as easily emphasise the continuity of an attitude: Gerlier, who was not very doctrinaire, never wanted to discourage anyone or any initiative as soon as he saw the quality of the pioneers, the hope they carried within them and the necessity of their undertaking. It was necessary, and even urgent. France in 1946 was a country where one in four voters voted Communist, and where the reputedly Marxist parties (PCF and SFIO) held two-thirds of the seats in the National Assembly. In the Lyon conurbation, 7 % of foremen and skilled workers and 1.4 % of O.S. regularly or occasionally practise the Catholic religion. It's obvious that the big battalions on this side have not been touched by Catholic Action or Christian trade unionism, and have only very distant relations with parish priests.

Authoritative without being authoritarian, Gerlier enjoyed advising and was well enlightened on these issues by men of the calibre of Abbé Ancel - who will be discussed later - and the theologians at Fourvière. During and after the war, the latter played an essential role in this "broad intellectual effervescence linked to the widespread perception of a new cultural situation. It was no longer necessary to be Christian against a world that was no longer Christian and had to become so again, but in a world where Christian identity was increasingly problematic". Should we be striving to rebuild a Christian city (the argument of Catholic Action) or should we be thinking only of bringing life to a secularised world (the argument of the worker priests)? Some, in love with logic or unsympathetic to the virtues of pluralism, felt that the two theses were radically mutually exclusive. Others, pragmatists, pastors first and foremost and gifted with a periscopal outlook, thought that the most urgent needs had to be met and that there was room for everyone in the enormous task of evangelisation that the Church in France had to undertake.

Gerlier belonged to the latter type, of course; he accepted parish priests in overalls or in overalls because for him there was no choice between the two formulas, Catholic Action and worker priests; his preference was for the former, but he was well aware, like Suhard, that "the Gospel had to be proclaimed to a revolution" and that what was at stake deserved exceptional means. In the long term, the Cardinal remained committed to the ACJF-type strategy. In the short term, he recognised the usefulness of the "working priests" tactic, provided that it was not presented as an absolute model of priestly life but as an exceptional formula imposed by circumstances.

A cardinal through thick and thin, he supported the commitment of working-class priests at a time when, in the midst of the Cold War, a global dispute between the Church in France and the Roman Curia was hardening. Two dates mark this hardening: the decree of the Holy Office of 1 July 1949, which renewed the condemnation of communism and enabled the methodical dismantling of companies that claimed to be "progressive" or that certain informants claimed to be "progressive" (we have seen how the catechist Joseph Colomb was saved at the last minute by Gerlier). The 1950 encyclical Humani generis, on the other hand, targeted exegetes, historians and philosophers, with Fourvière in the crosshairs (Gerlier had to play the saint-bernard to Father de Lubac, who was banned from teaching for ten years). As we can see, the experience of the worker priests did not develop in a climate of great serenity, all the more so as the media got hold of their case; the novel dedicated to them by Gilbert Cesbron, Les Saints vont en Enfer, was a best-seller.

But it was for fundamental reasons, independent of the immediate situation, that in 1953 Pope Pius XII informed the leaders of the Church in France of his intention to interrupt the experiment. Gerlier, along with Feltin from Paris and Liénard from Lille, immediately took the train. Having come to Rome expressly to dissuade the Pope, and convinced that they would succeed, it was they who were persuaded. Pius XII "had for himself the logic of a system" or, if we prefer, the logic of a coherent, integral and exclusive conception of the priesthood. There were two bases for this conception: firstly, the Tridentine conception, which made the priest a man apart; secondly, the militant conception of Leo XIII, the idea of the chaplain-lay tandem that founded Catholic Action. At the very most, the three Cardinals saved the future by not explicitly condemning the very principle of the priest at work.

Among the workers' priests who refused to submit in 1954 were, with a few exceptions, the teams in Lyon and Saint-Etienne. This was a great blow for Gerlier, and a cruel one for two reasons: "He had hoped that, through them, Christ and the Church would be able to penetrate more deeply into the heart of the working world; and, moreover, they were his specially loved sons. Without giving them reason, he refused to impose sanctions, retaining enough confidence in them and enough affection for them to believe patiently in their return one day.

The working-class priests were placed in the Church's reserve when the diocese of Lyon changed its borders, expanding eastwards and annexing the large working-class commune of Villeurbanne.

In Lyon itself, Gerlier succeeded not only in saving the future but also in continuing the experiment, in a more modest way, thanks to Abbé Ancel and his Prado priests. Alfred Ancel, a philosophy professor at the Institut Catholique de la rue du Plat, was elected superior of the Prado priests in 1942. Founded in the 19th century by Father Chevrier to evangelise the poor, the Prado community was vigorously taken in hand and developed by Ancel, who, in 1946, sent some Prado priests to work in factories. Gerlier gave his seal of approval to this initiative when, in 1947, he asked Pius XII to appoint Father Ancel as auxiliary bishop. In the working-class district of Gerland, Mgr Ancel developed an inter-parish patronage to welcome immigrant workers, as well as a model re-education centre (Jacques Gadille, Histoire des diocèses, le diocèse de Lyon, Paris 1983, p. 288). He also worked to establish the community throughout the world. (In 1965, with more than 700 members, it was present in 76 French dioceses and 14 foreign dioceses).

At the end of 1954, Mgr Ancel was authorised to set up a working community in Gerland that respected - at least Gerlier managed to persuade Rome to do so - the pontifical prohibitions of 1953: no trade union or political involvement and, in the great Lyonnais tradition of the canuts, manual work at home. No question of factories, no promiscuity with atheistic communism, and flexible working hours compatible with the exercise of traditional priestly activities. So it was that, together with two priests and two brothers from Prado, Mgr Ancel became the first working-class bishop in France. To deny him the epithet "worker" would be to forget that the industrial fabric of France was far from being limited to the world of factories, but was animated by a multitude of small subcontracting workshops - which is what Bishop Ancel's community was (Emile Poulat, Une Eglise ébranlée, Paris 1980, p. 137).

It was discreet, modest, but still too visible for certain Roman authorities. It is true that Gerlier, his colleagues in Lille and Paris and other French bishops did much to reopen the issue in high places when, at the end of 1958, they wrote a note stressing the need for a full-time priestly presence in factories and on building sites. In 1959, the priests of Prado received an order from the Holy Office to abandon all manual work. They immediately complied. It was then that Mgr Ancel made it clear that the apostolate in Japan (from where he had just returned) seemed to him, despite the exceptional difficulties, "less difficult than the apostolate in the French working class" (Emile Poulat). The other part of Gerland's work remained: welcoming immigrant workers. And in the France of 1959, this was not a particularly peaceful activity. It gave Gerlier the opportunity to reassert himself as a defender of human rights and also as a great lawyer who was adept at confounding some rather overzealous police officers.

In the Algerian war

1954 saw the abrupt end of the experience of priests working in factories; it was also the start of a war that had particular repercussions in the diocese of Lyon, where there were many Algerian workers. From an ecclesiastical point of view, the situation was complicated by the fact that Cardinal Gerlier had not only supported the efforts of Bishop Ancel and his pradosians to organise real social assistance for the Algerians: he had also authorised priests to live completely with them; better still, he had expressly delegated them to their service. "My brothers", he declared one day from the pulpit of his Primatiale, "as a bishop, I am responsible before God, who will hold me accountable, for all the inhabitants of this diocese and even for each and every one of them, even if they are Muslims".

This statement is based on the most sound doctrine; it also expresses great generosity and a great understanding of the condition of immigrants. Pierre-Marie Gerlier liked to repeat the words of one of them: "What hurts us is not being hungry or cold, but feeling despised". When nationalist movements such as the FLN took root in Lyon's Algerian community, the situation of several priests quickly became delicate. In the most difficult times, the cardinal always supported and defended them energetically, as he did for Témoignage chrétien in March 1958, when the paper had become the target of all those who envisaged only a military solution for Algeria.

The following October, a policeman from the Renseignements généraux in Lyon informed the press that fifteen or so Algerians who had been arrested and questioned had implicated three priests from the Prado. Abbés Carteron, Chaize and Magnin were accused of having acted as fund distributors for the FLN. In fact, Abbé Carteron had merely set up a mutual aid fund for the families of imprisoned Algerians. As for Abbés Chaize and Magnin, they had simply offered hospitality to this service by lending one of the Prado offices. There was nothing clandestine about this activity, which was well known to the superiors of the three accused priests, Bishop Ancel and the Cardinal himself.

While Abbé Magnin was being charged with undermining national security, Abbé Carteron waited until the end of the police investigation to appear directly before the examining magistrate; and he did so with the agreement of his superiors. In those days, strange things sometimes happened in certain police stations. From Rome, where he was detained by the conclave, Pierre-Marie Gerlier did not content himself with intervening to stop the proceedings. He went on the counter-attack and denounced the torture: "To back up these accusations, certain members of the police - I say certain members - did not hesitate to make the Muslim suspects sign statements whose falsehood is easy to discern. To achieve this, they did not hesitate to use violence and the most serious forms of abuse (...) I think I am entitled to say that some of those who were subjected to this treatment were put in a serious physical and moral state" (H. Hamon and P. Rotman, Les porteurs de valises, Paris 1981, p. 122).