A popular teacher

Extract (pages 94-95) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

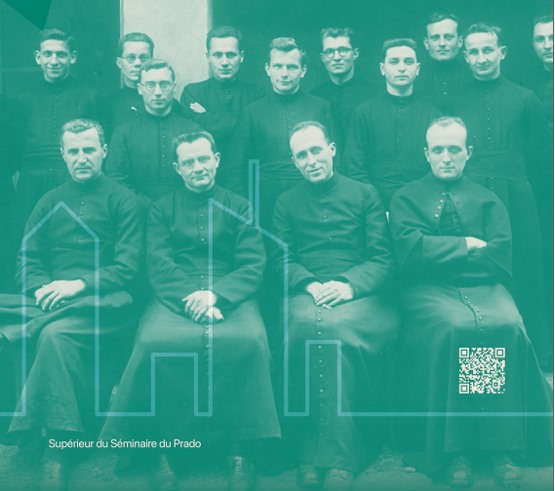

Alfred Ancel took his doctorate in Scholastic Philosophy at the Gregorian University on 18 June 1920. Having passed with summa cum laude, it is not surprising to find him teaching philosophy at the Prado Seminary from 1928 onwards. The old-timers still remember his twenty Thomistic theses clearly set out in a Latin that, although not that of Cicero, nevertheless required long sessions of revision for some. Father Ancel made it a point of honour to follow the Roman directives for seminaries. But he gave his all to teaching philosophy at the Facultés Catholiques de Lyon, where the rector, Mgr Fleury Lavallée, called him in October 1932. Until 1943, Cardinal Gerlier wrote, he was to give "a lively and profound teaching that won over young students, and whose excellence stemmed from both the intellectual loyalty of the teacher and his constant concern to touch souls".

Father Ancel, who was already absorbed by various tasks and often had to work through the night to prepare his lectures, was a real hit with his listeners. Many of them, such as Henri Lugagne, who became Bishop of Pamiers, will still remember him with pleasure many decades later... It wasn't just the philosophy students who remembered him, because Father Ancel also gave two major public lectures, which were reprinted several times in small booklets: one, in 1941, on "Dieu à la lumière de la raison" (God in the light of reason), and the other, in 1942, on "L'homme à la lumière de la raison" (Man in the light of reason). Their influence extended far beyond Lyon and its universities. But above all, his lectures revealed him as an orator. And therein lies the reason for the success of the lectures themselves. Father Ancel never read a text in a neutral voice, indifferent to his audience. He sought to reach out to his audience as if he wanted to enter into a friendly conversation with each of them. This is what attracted his students, as well as the Christian people in the parishes who listened to his homilies, or the young girls who attended the retreats he preached. All things considered, we can say of him what Mgr Blanchet wrote of a man whom Alfred Ancel himself recognised as a master of philosophy, Auguste Valensin: "For him, thought must be communicated and must not fear the test of dialogue (...). In his eyes, there is no knowledge that is well mastered and that the first person who comes along cannot benefit from.

General metaphysics

Extract (pages 95-96) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

A voluminous book entitled Métaphysique générale appeared long after the author had ceased his lectures. The work was praised in a number of specialist journals and received some glowing reviews, but did not have the same impact as La Pauvreté du Prêtre. Some saw it above all as "a magnificent collection of philosophical definitions and theses". Many seminary teachers, who did not always have sufficient preparation for their role, made it their favourite textbook. But, even more than La Pauvreté du Prêtre, this book with its austere subject suffered from a serious editorial problem, since it reproduced, in a hasty compilation, students' notes, as Father Ancel explained in the preface. We can imagine that in the early 50s, Father Ancel had even less time than at the time of the war to rework this work. The imprecise references to the authors consulted leave unsatisfied readers who have kept abreast of advances in philosophical thought, including Thomism. This is one of the reasons why this book hardly remained on the shelves of personal libraries and even gathered dust fairly quickly on those of the libraries of the major seminaries.

In these conditions, should we talk about it? We thought so. Indeed, from Alfred Ancel's point of view, the fact that he undertook the publication of this book in 1952-1953 proves that, although he recognised its serious limitations, he still considered its value to be justified. This book is therefore the state of his philosophical thought at the time when he had reached the full maturity of his age. Moreover, the fairly numerous notes he took the time to write in the peace and quiet of La Roche during the summer of 1952, while indicating here and there this or that addition that should have been developed, are above all interesting because they confirm an overall synthesis. It is therefore from this document, taken as such, that we can get an idea of the inner coherence of the ideas that animated Father Ancel throughout his life.

Whatever the value of the other sources that exist for learning about his thought - unpublished notes or various articles published between 1932 and 1950 - this book is essentially the fruit of fundamental teaching spread over more than ten years. It must therefore be concluded that there are very deep connections, albeit hidden from those who witness his actions alone, between the thought he developed in this book and the whole field of his subsequent activities. We believe that it is even on the condition that we have some grasp of the mainspring of his thought that we can critically assess his activities. Undoubtedly, as one of his most benevolent critics wrote in 1954, comparing Father Ancel to Saint Bonaventure, who had become Minister General of the Friars Minor and then Bishop: "Isn't there something wrong with asking questions of a philosopher who no longer has the leisure to philosophise? But it has to be said that Alfred Ancel, even as a teacher, loved dialogue above all, as he repeated to his students on 6 December 1932 before starting a course in Theodicy: "It seems to me that scholasticism requires close collaboration between teacher and students. Objections, requests for clarification: conversation rather than lectures".

It is in this spirit that we wish to undertake here a brief reflection on the content of the General Metaphysics, and thereby perhaps help a little to understand the purpose of existence.