"How beautiful is Jesus Christ! Father Chevrier expresses all his admiration and joy before the One he contemplates and by making Him contemplate," remarks Cardinal Garonne in a preface to the new edition of the book by the founder of Prado: Le prêtre selon l'Evangile ou le Véritable Disciple de Notre Seigneur Jésus Christ (The Priest according to the Gospel or the True Disciple of Our Lord Jesus Christ).

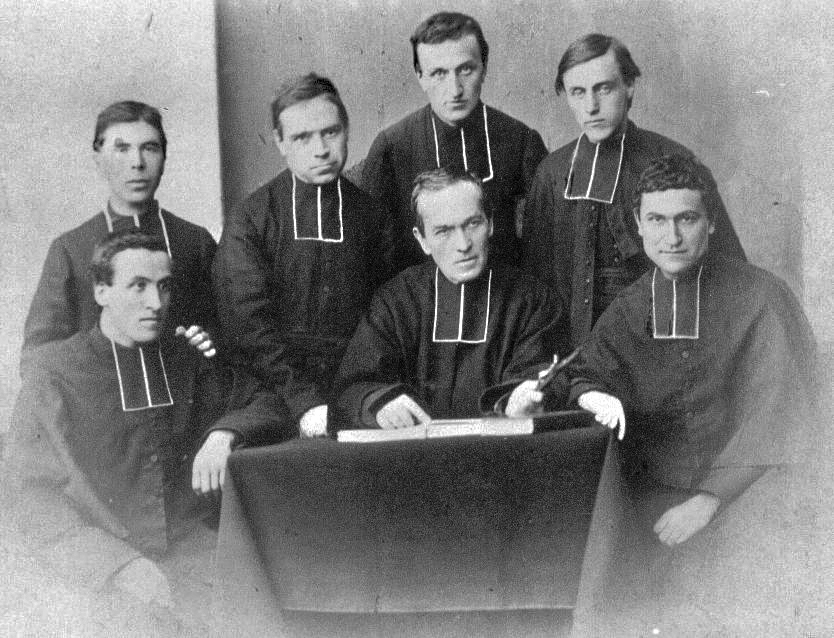

"How beautiful this man of God is", said Blessed Antoine Chevrier, speaking of the priest "according to Jesus Christ". From Rome, where he was finishing preparing his first four deacons for ordination, he sent them this message: "You are going to be great when you become priests, but you will have to be small at the same time to be truly new Jesus Christs on earth... How beautiful, but how difficult. Only the Holy Spirit can make us understand that".

"Evangelising the poor was the great mission of Jesus Christ on earth". For Father Chevrier, this was the mission of the "new apostles in the world" that he so much wanted to give to the Church. To begin with the poor, the first recipients of the Good News, is to be sure not to forget anyone.

Preparations

Father Chevrier's life bears the imprint of the world that shaped him. Antoine was born on 16 April 1826 into a modest family in the heart of Lyon. His father worked at the octroi office. His mother was a silk manufacturer. Originally from Dauphiné, she always showed an energetic temperament. She was reluctant to let her son go to the seminary, hoping for a better future for him. It was a parish vicar who suggested that Antoine Chevrier become a priest, which he readily accepted. After attending parish clerical school, he entered the major seminary of Saint Irénée in Lyon in 1846. He was 20 years old. He was ordained a priest on 25 May 1850. He was too young to have any vivid memories of the two Canuts revolts of 1831 and 1834. However, he did witness the events of the 1848 revolution. A group called "Les Voraces" even occupied the major seminary.

On leaving the seminary, his personal notes show his desire to become a good priest "who knows how to use everything for the Gospel. Because," he continued, "there is good to be done wherever I am, and however bad and wicked the men I have to lead may be, they are all called to salvation".

Beginnings

Ordained three days earlier, Abbé Chevrier crossed the Rhône to join the recently founded parish of Saint-André de la Guillotière. The population was growing rapidly, with people from the surrounding countryside and provinces crowding into the church.

Ordained three days earlier, Abbé Chevrier crossed the Rhône to join the recently founded parish of Saint-André de la Guillotière. The population was growing rapidly, with people from the surrounding countryside and provinces crowding into the church.

brick houses between factories and workshops. The metal, textile and chemical industries were booming. The first railway lines ran from Lyon. A village in the Dauphiné region with 7,000 inhabitants in 1815, this suburb of Guillotière had more than 40,000 by the time it became part of the city of Lyon in 1852. By 1856, this number had doubled again. The young vicar found himself at the heart of the industrial expansion and its many problems. He devoted himself to his ministry to the point of falling ill. He discovered the material and moral misery of the workers and suffered greatly from the distance separating him from the people. In December 1855, he had to rest for four months before returning to Saint-André.

A decisive year

1856, on 31 May, the district was flooded by the overflowing Rhône. The parish clergy were at the forefront of the rescue effort. Abbé Chevrier took a very active part in the rescue effort. His reputation for dedication grew. He became even more aware of the scale of the misery affecting the people. Events brought him face to face with the lives of local families, with their insalubrious housing and endless working days, including Sundays. While faith in God coloured people's mentalities, it was above all religious "ignorance" that scandalised him, even more than the frequent hostility towards priests and the Church. For them, priests are from another world. He suffered to see his ministry bear little fruit. Yet he was very busy. His parish priest let him perform most of the baptisms, marriages and funerals. On the other hand, he opposed the meetings of a group of young people that Abbé Chevrier had brought together to become "apostles".

1856, on 31 May, the district was flooded by the overflowing Rhône. The parish clergy were at the forefront of the rescue effort. Abbé Chevrier took a very active part in the rescue effort. His reputation for dedication grew. He became even more aware of the scale of the misery affecting the people. Events brought him face to face with the lives of local families, with their insalubrious housing and endless working days, including Sundays. While faith in God coloured people's mentalities, it was above all religious "ignorance" that scandalised him, even more than the frequent hostility towards priests and the Church. For them, priests are from another world. He suffered to see his ministry bear little fruit. Yet he was very busy. His parish priest let him perform most of the baptisms, marriages and funerals. On the other hand, he opposed the meetings of a group of young people that Abbé Chevrier had brought together to become "apostles".

Probably in June 1856, he met Camille Rambaud. This young middle-class Lyonnais had put himself at the service of the poor, living like them and in their midst. He built the "Cité de l'Enfant Jésus", a sort of emergency housing estate. Antoine Chevrier was overwhelmed by his visit and said on his return to the presbytery: "I saw John the Baptist in the desert!

On Christmas night 1856, he meditated in front of the cot. "The Word became flesh and dwelt among us". On 25 December of that year, something was born, a very inner event that he called his conversion.

He had been a priest for six years, in an ordinary parish ministry, appreciated by the faithful. I said to myself: the Son of God came down to earth to save mankind and convert sinners. And yet what do we see? How many sinners there are in the world! Men continue to damn themselves. So I decided to follow Our Lord Jesus Christ more closely to make myself more capable of working effectively for the salvation of souls". Then he continued with a founding intuition: "And my desire is that you too should follow Our Lord more closely".

He had been a priest for six years, in an ordinary parish ministry, appreciated by the faithful. I said to myself: the Son of God came down to earth to save mankind and convert sinners. And yet what do we see? How many sinners there are in the world! Men continue to damn themselves. So I decided to follow Our Lord Jesus Christ more closely to make myself more capable of working effectively for the salvation of souls". Then he continued with a founding intuition: "And my desire is that you too should follow Our Lord more closely".

So something began at Christmas 1856. Antoine Chevrier conceived the project of living as a priest according to the Gospel to respond to the immense apostolic needs he saw around him. "It was at Saint-André that Prado was born", he would say. Deployment of the charism

In fact, Antoine Chevrier went through another four years of trial and error. Decisive but cautious, he took advice from different people. As early as 1857, he consulted the Curé d'Ars. The two men held each other in high esteem. Abbé Chevrier recognised in Jean-Marie Vianney an older brother who was doing in his own way what he felt called to do. He would do it differently because they were not of the same generation. And the situation of a vicar in a working-class suburb, at the heart of the emerging industrial and technical world, was not that of a village priest. In August, he left parish ministry to become chaplain to the "Maison de l'Enfant Jésus" founded by Camille Rambaud for incurable children, and to the "Cité" of the same name, a social housing project for workers. He taught catechism to the children with the help of a few lay people, including Marie Boisson, a young silk worker who was to become the first head of the Prado sisters. Father Chevrier and his companions soon realised that the situation was not viable, as Camille Rambaud's project and their own were too different.

In fact, Antoine Chevrier went through another four years of trial and error. Decisive but cautious, he took advice from different people. As early as 1857, he consulted the Curé d'Ars. The two men held each other in high esteem. Abbé Chevrier recognised in Jean-Marie Vianney an older brother who was doing in his own way what he felt called to do. He would do it differently because they were not of the same generation. And the situation of a vicar in a working-class suburb, at the heart of the emerging industrial and technical world, was not that of a village priest. In August, he left parish ministry to become chaplain to the "Maison de l'Enfant Jésus" founded by Camille Rambaud for incurable children, and to the "Cité" of the same name, a social housing project for workers. He taught catechism to the children with the help of a few lay people, including Marie Boisson, a young silk worker who was to become the first head of the Prado sisters. Father Chevrier and his companions soon realised that the situation was not viable, as Camille Rambaud's project and their own were too different.

His priority was "an entirely spiritual ministry". His three young companions were determined to devote themselves, like him, to catechising poor children: Marie was 22; Pierre Louat, a notary's clerk, was 27; and Amélie Visignat, 22, had joined the Cité to teach girls' catechism. To Father Chevrier's surprise, Marie did not hesitate to consult Cardinal de Bonald, who received her warmly and encouraged her simple, resolute approach.

At the end of that same year, 1857, the man who became known as Father Chevrier made a retreat at the end of which he made a resolution that expressed the meaning of his priesthood: "Studying Jesus in his mortal life, in his Eucharistic life, will be my entire study. Imitating Jesus is therefore my sole aim, the end of all my thoughts and actions, the object of all my wishes and desires. Without this, I will never make a good priest or work effectively for the salvation of souls. Studying Jesus is my whole study". He left more than 20,000 handwritten pages of his "Study of Our Lord Jesus Christ", worked assiduously in prayer and with the threefold aim of advancing himself in a life of true discipleship, providing solid and simple food for "teaching catechism" and forming apostles for the evangelical service of the poor.

The work of first communion

At the end of 1859, Père Chevrier left Cité Rambaud. In the Guillotière district, he would sometimes pass a seedy dance hall called the Prado. Each time he asked God to give it to him. One day in 1860, the hall was "for rent or for sale". With the help of two confreres, Father Chevrier paid the rent; a Protestant contractor offered to send workmen to fit out the premises. The hall was huge: a thousand people could dance to their hearts' content. First of all, Father Chevrier had the chapel fitted out in the centre; on either side were places to house poor and ignorant teenagers, whom he would take in for six-month periods in order to give them "a sense of their own greatness", lead them to First Communion and provide them with a minimum of instruction. Father Chevrier took possession of the premises on 10 December 1860. Prado was founded. Sister Marie took charge of the girls. Around Easter 1861, Prado was home to ten girls and fifteen boys. A few years later, the house had to feed more than two hundred people. Father Chevrier would go so far as to beg on days when bread was in short supply; he never wanted the children to be given work on the spot, as was common at the time. The little time they spent at Prado was too precious in his eyes for them to be kept from discovering "their duties as men and as Christians".

"The need of the times and of the Church".

In 1865, Father Chevrier began to carry out "a work he had wanted to do for many years": a school for the training of priests. For him, putting seminarians in contact with the children of Prado was the best way of training poor priests to evangelise the poor. During the year, an exchange of letters with Abbé Gourdon led him to think that Gourdon might join him. At the end of January 1866, Father Chevrier realised that the archbishopric would not give the authorisation he had requested. In May, he bought a house and a plot of land on the other side of the street, opposite the Prado. The sisters moved in with the First Communion girls. Prado was then able to welcome the seminarians. Father Chevrier spent a considerable amount of time training them. He wrote a book for them, which he left unfinished: Le prêtre selon l'Evangile ou le Véritable Disciple de Notre Seigneur Jésus Christ. In this he was faithful to the grace of Christmas 1856 "when he received a very special insight into the poverty of Our Lord and his special vocation to train poor priests". He provided this training while continuing the work of first communion and, from 1867 to 1871, taking charge of the parish of Moulin à Vent, with the aim of carrying out "the work of poor parishes". With the agreement of his archbishop, he also spent several months in Rome to complete the training of the first deacons.

In 1878, Father Chevrier experienced the ordeal of seeing the work he had cherished most crumble. The first four priests he had trained wanted to leave, one to the Trappist monastery, another to the Grande Chartreuse, another as a missionary in China... He wrote a painful letter to Father Jaricot: "I will have the consolation of having made Trappists, Carthusians and missionaries, if I have not succeeded in making catechists; although, it seems to me, that must be the need of the times and of the Church today".

The letter was signed: "Your brother in Jesus Christ abandoned on the cross". A few months later, he fell seriously ill and had to stop working. Treated at Limonest, he was taken, at his request, on 29 September to Prado, where he died on 2 October 1879.

"Sacerdos Alter Christus

This theme recurs frequently in the writings of Father Chevrier. For example, in a letter to Abbé Gourdon: "The priest is another Jesus Christ. Pray that I may truly become one. I feel that I am so far from this beautiful model that I sometimes get discouraged, so far from his poverty, so far from his death, so far from his charity. Pray and let us pray together that we may become conformed to our beautiful model". We find it again in one of his last texts: "Our particular motto is 'Sacerdos Alter Christus'. To imitate Jesus Christ, to conform ourselves to him, to follow him as closely as possible: this is our desire and the great goal of our life". He found the formula in the Holy Fathers, he says. It is more likely to be found in the literature of the time. But that's not the point. Father Chevrier simply thought that ordination to the priesthood had placed within him a free gift from God, a grace to be made to bear fruit. To do this, he had to "know, love and follow Jesus Christ". To know him by studying the Gospel, because it was written so that today we can walk the path that the apostles travelled with him. Knowing him leads us to love him more and invites us to conform our lives to his, and thus to follow him in the mission he has received from his Father. For him, the formula is not an abstract theological definition but a motto to guide his life, a becoming to be realised day by day.

"To know Jesus Christ is everything. The rest is nothing. Whoever has found Jesus Christ has found the greatest treasure. He has found wisdom, light, life, peace, joy, happiness on earth and in heaven, the solid foundation on which to build. On the basis of this unique knowledge, Antoine Chevrier, as a true educator of the faith, initiated a spiritual and pastoral pedagogy that put "the interior first": "It is the Holy Spirit who produces Jesus Christ in us". "Isn't that what we're here for, and that alone: to know Jesus and his Father and to make him known to others? I work at this with joy and happiness. Knowing how to talk about God and make him known to the poor and ignorant is our life and our love.

On the walls of an old stable, where there is still today a manger for the animals, Father Chevrier had the idea of painting, with twelve young people who were thinking of becoming priests, a picture, which the pradosians got into the habit of calling the Tableau de Saint-Fons: the Crib, the Calvary, the Tabernacle. The layout of the site led him to place the mystery of the Eucharist at the centre of the triptych. He did not invent the idea of summing up the Gospel ideal in this way. But the commentary he gives is his own, and in particular the threefold statement: "the priest is a stripped man, the priest is a crucified man, the priest is an eaten man". The last sentence has made a fortune. But we can only grasp its full meaning if we read and live what Father Chevrier himself lived. Like his Master and Lord. Without poverty and suffering, an all-consuming activity will never "become good bread".

On the walls of an old stable, where there is still today a manger for the animals, Father Chevrier had the idea of painting, with twelve young people who were thinking of becoming priests, a picture, which the pradosians got into the habit of calling the Tableau de Saint-Fons: the Crib, the Calvary, the Tabernacle. The layout of the site led him to place the mystery of the Eucharist at the centre of the triptych. He did not invent the idea of summing up the Gospel ideal in this way. But the commentary he gives is his own, and in particular the threefold statement: "the priest is a stripped man, the priest is a crucified man, the priest is an eaten man". The last sentence has made a fortune. But we can only grasp its full meaning if we read and live what Father Chevrier himself lived. Like his Master and Lord. Without poverty and suffering, an all-consuming activity will never "become good bread".

For no other reason than to love the people God loves, to the point of a passion to "give them the faith" he had received, Father Chevrier, himself deeply influenced by the holiness of Francis of Assisi, was faithful to the programme he had set himself after Christmas night 1856: "To be with the poor, to live with them, to die with them". He died at the age of fifty-three. The people of Guillotière asked the prefecture to bury him in the Prado chapel. "Three hundred priests attended the funeral and it was estimated that ten thousand people followed the convoy. It was also said that fifty thousand people came to watch the procession".

Prado from Chevrier to the present day

The Association of Diocesan Priests of Prado, which for a long time was based in Lyon, developed after the Second World War in many dioceses in France, Spain, Italy and the Middle East, particularly under the impetus of Bishop Ancel. Today it is present in more than fifty countries. The family has expanded to include sisters and consecrated lay men and women. Deacons and more and more of the lay faithful around the world are also inspired by this message. Father Chevrier was beatified by Pope John Paul II in Lyon on 4 October 1986. He made a pilgrimage to his tomb on 7 October.

The Association of Diocesan Priests of Prado, which for a long time was based in Lyon, developed after the Second World War in many dioceses in France, Spain, Italy and the Middle East, particularly under the impetus of Bishop Ancel. Today it is present in more than fifty countries. The family has expanded to include sisters and consecrated lay men and women. Deacons and more and more of the lay faithful around the world are also inspired by this message. Father Chevrier was beatified by Pope John Paul II in Lyon on 4 October 1986. He made a pilgrimage to his tomb on 7 October.

The Chapel, in all its prayerful simplicity, welcomes many pilgrims from France, Italy, Spain and many other countries.

Roland Letournel

Robert Daviaud

Born 16 April 1826 in Lyon (Rhône), died 2 October 1879 in Lyon (Rhône); priest in the diocese of Lyon; founder of the Prado charity for poor children and the Association des Prêtres du Prado.

Born 16 April 1826 in Lyon (Rhône), died 2 October 1879 in Lyon (Rhône); priest in the diocese of Lyon; founder of the Prado charity for poor children and the Association des Prêtres du Prado. It prepared them for their First Communion in the form of an intensive and accelerated catechism course. The Rhône Academic Inspectorate having authorised him to open a school, they also received basic instruction in reading, writing and arithmetic. This "small boarding school for the poor" (Ms X,15a) took in between 2,300 and 2,400 children, two-thirds of them boys and around one-third girls, from 10 December 1860, the day Father Chevrier bought the Prado, until 2 October 1879, the day he died.

It prepared them for their First Communion in the form of an intensive and accelerated catechism course. The Rhône Academic Inspectorate having authorised him to open a school, they also received basic instruction in reading, writing and arithmetic. This "small boarding school for the poor" (Ms X,15a) took in between 2,300 and 2,400 children, two-thirds of them boys and around one-third girls, from 10 December 1860, the day Father Chevrier bought the Prado, until 2 October 1879, the day he died. Antoine Chevrier's writings - his letters, his preaching, his commentaries on the Gospel and even Le Véritable Disciple, the book he wrote for the training of his priests - do not contain an analysis of the working-class conditions of his time.

Antoine Chevrier's writings - his letters, his preaching, his commentaries on the Gospel and even Le Véritable Disciple, the book he wrote for the training of his priests - do not contain an analysis of the working-class conditions of his time. The Lyon newspaper Le Progrès, which at the time was not very sympathetic to the Church, wrote in its edition of Thursday 9 October 1879:

The Lyon newspaper Le Progrès, which at the time was not very sympathetic to the Church, wrote in its edition of Thursday 9 October 1879:

Ordained three days earlier, Abbé Chevrier crossed the Rhône to join the recently founded parish of Saint-André de la Guillotière. The population was growing rapidly, with people from the surrounding countryside and provinces crowding into the church.

Ordained three days earlier, Abbé Chevrier crossed the Rhône to join the recently founded parish of Saint-André de la Guillotière. The population was growing rapidly, with people from the surrounding countryside and provinces crowding into the church. 1856, on 31 May, the district was flooded by the overflowing Rhône. The parish clergy were at the forefront of the rescue effort. Abbé Chevrier took a very active part in the rescue effort. His reputation for dedication grew. He became even more aware of the scale of the misery affecting the people. Events brought him face to face with the lives of local families, with their insalubrious housing and endless working days, including Sundays. While faith in God coloured people's mentalities, it was above all religious "ignorance" that scandalised him, even more than the frequent hostility towards priests and the Church. For them, priests are from another world. He suffered to see his ministry bear little fruit. Yet he was very busy. His parish priest let him perform most of the baptisms, marriages and funerals. On the other hand, he opposed the meetings of a group of young people that Abbé Chevrier had brought together to become "apostles".

1856, on 31 May, the district was flooded by the overflowing Rhône. The parish clergy were at the forefront of the rescue effort. Abbé Chevrier took a very active part in the rescue effort. His reputation for dedication grew. He became even more aware of the scale of the misery affecting the people. Events brought him face to face with the lives of local families, with their insalubrious housing and endless working days, including Sundays. While faith in God coloured people's mentalities, it was above all religious "ignorance" that scandalised him, even more than the frequent hostility towards priests and the Church. For them, priests are from another world. He suffered to see his ministry bear little fruit. Yet he was very busy. His parish priest let him perform most of the baptisms, marriages and funerals. On the other hand, he opposed the meetings of a group of young people that Abbé Chevrier had brought together to become "apostles". He had been a priest for six years, in an ordinary parish ministry, appreciated by the faithful. I said to myself: the Son of God came down to earth to save mankind and convert sinners. And yet what do we see? How many sinners there are in the world! Men continue to damn themselves. So I decided to follow Our Lord Jesus Christ more closely to make myself more capable of working effectively for the salvation of souls". Then he continued with a founding intuition: "And my desire is that you too should follow Our Lord more closely".

He had been a priest for six years, in an ordinary parish ministry, appreciated by the faithful. I said to myself: the Son of God came down to earth to save mankind and convert sinners. And yet what do we see? How many sinners there are in the world! Men continue to damn themselves. So I decided to follow Our Lord Jesus Christ more closely to make myself more capable of working effectively for the salvation of souls". Then he continued with a founding intuition: "And my desire is that you too should follow Our Lord more closely". In fact, Antoine Chevrier went through another four years of trial and error. Decisive but cautious, he took advice from different people. As early as 1857, he consulted the Curé d'Ars. The two men held each other in high esteem. Abbé Chevrier recognised in Jean-Marie Vianney an older brother who was doing in his own way what he felt called to do. He would do it differently because they were not of the same generation. And the situation of a vicar in a working-class suburb, at the heart of the emerging industrial and technical world, was not that of a village priest. In August, he left parish ministry to become chaplain to the "Maison de l'Enfant Jésus" founded by Camille Rambaud for incurable children, and to the "Cité" of the same name, a social housing project for workers. He taught catechism to the children with the help of a few lay people, including Marie Boisson, a young silk worker who was to become the first head of the Prado sisters. Father Chevrier and his companions soon realised that the situation was not viable, as Camille Rambaud's project and their own were too different.

In fact, Antoine Chevrier went through another four years of trial and error. Decisive but cautious, he took advice from different people. As early as 1857, he consulted the Curé d'Ars. The two men held each other in high esteem. Abbé Chevrier recognised in Jean-Marie Vianney an older brother who was doing in his own way what he felt called to do. He would do it differently because they were not of the same generation. And the situation of a vicar in a working-class suburb, at the heart of the emerging industrial and technical world, was not that of a village priest. In August, he left parish ministry to become chaplain to the "Maison de l'Enfant Jésus" founded by Camille Rambaud for incurable children, and to the "Cité" of the same name, a social housing project for workers. He taught catechism to the children with the help of a few lay people, including Marie Boisson, a young silk worker who was to become the first head of the Prado sisters. Father Chevrier and his companions soon realised that the situation was not viable, as Camille Rambaud's project and their own were too different. On the walls of an old stable, where there is still today a manger for the animals, Father Chevrier had the idea of painting, with twelve young people who were thinking of becoming priests, a picture, which the pradosians got into the habit of calling the Tableau de Saint-Fons: the Crib, the Calvary, the Tabernacle. The layout of the site led him to place the mystery of the Eucharist at the centre of the triptych. He did not invent the idea of summing up the Gospel ideal in this way. But the commentary he gives is his own, and in particular the threefold statement: "the priest is a stripped man, the priest is a crucified man, the priest is an eaten man". The last sentence has made a fortune. But we can only grasp its full meaning if we read and live what Father Chevrier himself lived. Like his Master and Lord. Without poverty and suffering, an all-consuming activity will never "become good bread".

On the walls of an old stable, where there is still today a manger for the animals, Father Chevrier had the idea of painting, with twelve young people who were thinking of becoming priests, a picture, which the pradosians got into the habit of calling the Tableau de Saint-Fons: the Crib, the Calvary, the Tabernacle. The layout of the site led him to place the mystery of the Eucharist at the centre of the triptych. He did not invent the idea of summing up the Gospel ideal in this way. But the commentary he gives is his own, and in particular the threefold statement: "the priest is a stripped man, the priest is a crucified man, the priest is an eaten man". The last sentence has made a fortune. But we can only grasp its full meaning if we read and live what Father Chevrier himself lived. Like his Master and Lord. Without poverty and suffering, an all-consuming activity will never "become good bread". The Association of Diocesan Priests of Prado, which for a long time was based in Lyon, developed after the Second World War in many dioceses in France, Spain, Italy and the Middle East, particularly under the impetus of Bishop Ancel. Today it is present in more than fifty countries. The family has expanded to include sisters and consecrated lay men and women. Deacons and more and more of the lay faithful around the world are also inspired by this message. Father Chevrier was beatified by Pope John Paul II in Lyon on 4 October 1986. He made a pilgrimage to his tomb on 7 October.

The Association of Diocesan Priests of Prado, which for a long time was based in Lyon, developed after the Second World War in many dioceses in France, Spain, Italy and the Middle East, particularly under the impetus of Bishop Ancel. Today it is present in more than fifty countries. The family has expanded to include sisters and consecrated lay men and women. Deacons and more and more of the lay faithful around the world are also inspired by this message. Father Chevrier was beatified by Pope John Paul II in Lyon on 4 October 1986. He made a pilgrimage to his tomb on 7 October.