Extracts from Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

Family soil

Extract (page 18) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

Alfred was born in Lyon, at 26 Place Bellecour, on 22 October 1898. Like his sister, he was baptised in the parish of Saint-Bonaventure a few days later, on the 29th. Marguerite was born in 1902; Joseph, who became a priest, followed in 1904. Then there was Jean, who was born on 29 January 1908, just as Alfred was entering the "Chartreux" in Croix-Rousse for his secondary education, and died young on 30 March 1932, when he too had just been ordained a priest. Finally, there was Henri, in 1911, who was to succeed Gustave Ancel as manager of the Villeurbanne plant. You have to go through this family's photo album to get an idea of how their material well-being went hand in hand with a very Lyonnais interiority, a tenacity in the sense of effort, and deep-rooted Christian feelings. It was, as a chronicler wrote after Abbé Jean's death, "one of those families (...) where one believes as one breathes; one speaks of things of the soul and of faith as naturally as possible".

The choice of the Institut des Chartreux for the education of the four Ancel sons may also provide useful information about the state of mind of their parents... They did not belong to the current of social Catholicism that had emerged towards the middle of the century. Admittedly ultramontane in outlook, they were, like the vast majority of Catholics in Lyon, faithful readers of the conservative daily newspaper Le NouvellisteMr Ancel accepted the son of the newspaper's director, Félix Rambaud, as his son-in-law. However, they were clearly distinct from the legitimist current which was then feeding the ranks of Action Française.

They had rallied to the Republic without hesitation as soon as Leo XIII had asked the Catholics of France to do so in his famous Encyclical Letter In the midst of solicitude of 16 February 1892. It was therefore quite natural, because they belonged to the business bourgeoisie, which was more 'liberal' than the bourgeoisie of the gowns, that they had sent their sons to the 'Chartreux' rather than to the Jesuits.

The Institution des Chartreux, on the southern slope of the Croix-Rousse, not far from the Ancel property on rue Chazière, had been founded in 1825 by a priest from the "Society of Saint Irénée", a priestly institute created by Cardinal Fesch for the needs of the "interior mission" in his diocese. As early as 1848, this school had distinguished itself by a gesture of solidarity with the workers, and, "in the following phase, the Carthusian monks showed themselves to be deliberately liberal, open to modern ideas and, as a result, sympathetic to the republicans themselves". If it is true that this secondary school was for a time subject to the influence of Action Française, it was only in the final years before its condemnation by Pius XI in 1926. Alfred Ancel had left the school in 1915 after passing his baccalauréat ès lettres with flying colours. What was life like for a young boarder at the Carthusian monastery at the turn of the century? Studious and even pious, no doubt. Alfred collected first prizes in all the subjects taught. He didn't shy away from sport and, with his cheerful nature, took part in his classmates' games without reticence. Pope Pius X had encouraged children to receive Holy Communion, so Alfred and his classmate Georges Finet regularly attended Wednesday and Friday Masses in the school chapel, which had once been built as a replica of the Holy Chapel. They had made their First Communion on Pentecost morning in June 1909. Cardinal Couillé, Archbishop of Lyon, confirmed them that same day in the afternoon, and in the evening there was a third ceremony: the consecration of the young communicants to the Blessed Virgin.

All this was so natural when you were a young schoolboy from a Christian family... Deep down, Alfred Ancel had no feelings of rejection for the education he had received. But in his heart, the ambition of social success outweighed everything else. His dream, over and above running his father's factory, was to be as successful in life as his results at school allowed him to be. That's why, when Father Favier, his class teacher in the ninth year, asked him, as he did all his pupils, "Tell me, Alfred, what are you going to do when you grow up? Why don't you become a priest?", the teenager replied in the negative, as if the question were completely absurd.

However, it was to Les Chartreux that Alfred Ancel returned to be ordained a priest on 8 July 1923. Two years before his death, he was still celebrating the sacrament of Confirmation there, as he had done in 1947 when, having just been ordained bishop, he said to the teenagers at his former college: "You belong to the bourgeoisie. Never forget the duties that this gives you". He himself never forgot that. He never harboured any resentment against his background. Everything we know about it shows just how much he owed to it in terms of his human upbringing, his character - so much like that of his paternal grandfather, always ready to overlook the faults of those around him - his religion too, of course, and even the contrasting nuances of his spiritual life. Although Alfred Ancel had to break certain bonds during his astonishing journey in the Church of Vatican II, and although he sometimes disconcerted his contemporaries with the increasingly incisive choices that the Gospel imposed on him, he never 'renounced' them. Until the evening of his life, his nephews and nieces (of both generations) remember the warmth of his welcome and the affectionate interest with which he listened to them. When, as Auxiliary Bishop of Lyon and Superior of the Prado, he was overwhelmed with various tasks, he would go up to his brother Henri's house at the Croix-Rousse, and Henri would invite him to work in the living room until lunchtime. Then, when the time came, Uncle Alfred would cross the threshold into the dining room, and there, suddenly forgetting all his burdens, he would be seen smiling and fully engaged in the family conversation. He also ate with a very good appetite, as when he was a seminarian, his visits to the Croix-Rousse alarmed the cook, who always wondered if she had made enough!

He certainly loved the house on the Croix-Rousse, with its shady park through which, in his childhood, you could descend the slope via an underground passage to the banks of the Saône. But he also had many other memories of the family holiday properties he and his brothers and sisters would visit, either in Quiberon or in the Alpilles, near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

From time to time, quite a few cousins from the maternal branch would join the Ancel children. Most of them went to the house in Chaponost during the "little holidays" of All Saints' Day and Candlemas. Alfred's closest friends were his cousins, of Polish origin on their father's side: Georges Lewandowski and his sister Annie, and Nelly Boissonnet, who was born the same year as him, although she was actually his aunt. These older members of the younger generation sometimes extended the evening conversations, as people like to do at that age. Little plays were put on for the pleasure of displaying budding talent within the family circle. Alfred loved Chaponost. Nelly will remember for the rest of her life the moment when, on the day of her ordination as a bishop, her cousin put his hand on her shoulder and said simply: "Chaponost". Annie Lewandowski, who was barely his junior, was also very fond of her cousin. He often laughed later when people reminisced about the time when they wanted to "marry" him and this young girl full of vitality... who had become Prioress General of a congregation of contemplative nuns.

In short, it was a happy adolescence.

Read also Volunteers (page 24, click here).

Volunteers

Extract (page 24) of Mgr Olivier de Berranger, Alfred Ancel, a man for the Gospel, 1898-1984, Centurion, 1988.

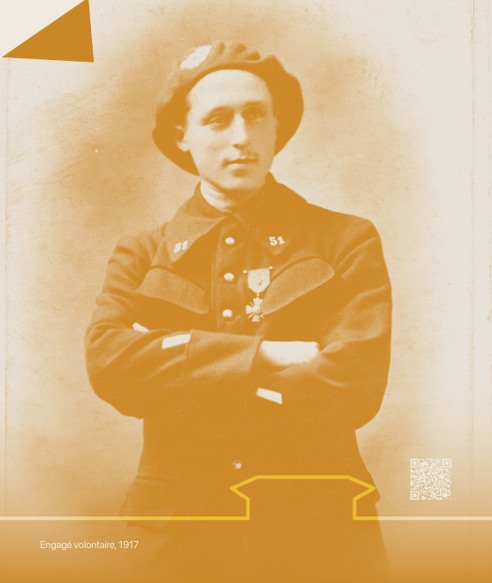

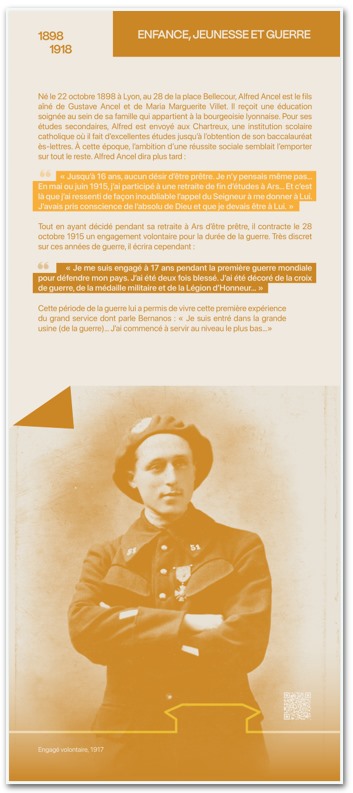

Let's stop for a moment and look at this young man of 17 who, among others - but the only one of his generation to become a bishop by having fought in the 1914 war as a volunteer - took the risk of giving his life to defend his country. He had already reached his full height of 1.73 metres. He has a proud face and a touch of amusement in his eyes. He stands up straight and, deep inside himself, carries the secret of the "absolute of God" of which he has become aware. Deep down, he is giving himself up to God. But he knows that such a "surrender" does not exclude giving himself to others and loving his country. On the contrary, he understands them and draws them in.

"I enlisted at the age of 17 during the First World War to defend my country. I was wounded twice. I was awarded the Croix de Guerre, the Military Medal and the Légion d'Honneur. Excuse me for saying all this, but people are so easily accused of anti-militarism that I had to make my position clear...". At the age of 75, Father Ancel recalls this distant past before saying his "no" to the military dictatorship that took hold in Chile after the fall of Allende. Generally speaking, he did not boast much about this period of his youth, although he did not repudiate it. When, during the third and fourth sessions of the Second Vatican Council, the important debate took place on the conditions for world peace, he intervened publicly on two occasions to show how a well-understood patriotism could be combined with the needs of international authority. But he confided to those close to him that if he had to do it all over again, he would not have enlisted, because of the witness a priest must give to the transcendent and the definitive odiousness of war. However, he added, "I was not yet a seminarian at the time".

The young man of 17 who enlisted was convinced that his country was within its rights. Referring to the many Frenchmen who, in 1914-1918, "had magnificently sacrificed their lives", he added this judgement, which must have matured in him between the two wars: "We have seen in France a spiritual resurrection that has struck with admiration those who thought our country had been definitively lost to secularism".

But after the initial period of enthusiasm that must have followed his enlistment in 1915, what feelings did the young volunteer have when he came into contact with reality? We can guess them from the letters, full of humour, that he wrote to Nelly Boissonnet. They are dated but not located, because of "military secrecy":

"Sunday 18th October 1916. My dear old aunt, I received your kind card which has come to join me in the far less kind place we occupy. However, its quality is praised and, according to a newspaper from the front, we are in a ferruginous resort like nowhere else. The treatment may be a bit radical, but everyone who comes out of it is doing well. You asked me about our life at the front. For those at the back, it's covered by a certain halo, which, alas, is hardly the case here. One wonders how glory can come walking through this mud and adorn troops full of vermin. At first sight, what characterises the "poilu" (pilosus vulgarisIn the natural history of the twentieth century), it is that he is a grognard: there is no worse insult that can be given to him than to say that he is a patriot. And then there are the phrases that keep coming back: "We're sold out to Germany" or: "If the Krauts come, we'll all surrender...". "If we have to attack, I refuse to get out of the trench. That's for ordinary days, but on days when it's raining, when you're short of a quart of wine, when the juice isn't very sweet, then it's the debacle."

"What's coming to surrender with me?"

"When you hear that the first time it's shocking, then when you've seen the Krauts attack and instead of surrendering you receive them cleanly with rifle fire, when for the attack everyone marches in line as if on parade, when finally after a lot of shouting everything is done exactly, then you understand what the 'poilu' is worth.

But that doesn't sound much like what the newspapers are saying.

Read also Family soil (page 18, click here).